Phosphate Binders: What They Are and How They Work

When dealing with phosphate binders, medications that bind dietary phosphate in the gut, preventing its absorption into the bloodstream. Also called phosphate sequestrants, they are essential for people with chronic kidney disease, a progressive loss of kidney function that reduces the body’s ability to excrete phosphorus. In CKD, high serum phosphorus triggers bone and heart problems, so binders act as a first‑line defense.

Why Phosphate Control Matters

High phosphorus levels drive secondary hyperparathyroidism, excessive production of parathyroid hormone caused by low calcium and high phosphate in kidney disease. This hormone pulls calcium from bones, weakening them and raising cardiovascular risk. By lowering phosphate absorption, binders indirectly calm the parathyroid glands, creating a safer biochemical environment. The relationship can be summed up as: phosphate binders reduce serum phosphorus, which lessens secondary hyperparathyroidism, which in turn protects bone health.

Several binder families exist, each with its own strengths. The most common non‑calcium option is sevelamer, a polymer that binds phosphate without adding extra calcium, making it suitable for patients at risk of vascular calcification. Calcium‑based binders like calcium acetate are cheap but can increase calcium load, while lanthanum carbonate offers another metal‑based alternative with minimal tablet burden. Choosing the right binder depends on lab results, dietary habits, and individual tolerance.

Beyond binders, calcimimetics, drugs that mimic calcium and suppress parathyroid hormone secretion can be paired with binders to fine‑tune mineral balance. Calcimimetics lower PTH levels, which can reduce the phosphate load the body needs to handle. In practice, clinicians often use a binder‑plus‑calcimimetic combo for patients with stubborn hyperphosphatemia or severe secondary hyperparathyroidism. This synergy exemplifies the triple: binders control phosphate intake, calcimimetics curb PTH, and together they protect bone and heart health.

Dietary phosphate restriction works hand‑in‑hand with medication. Processed foods, colas, and cheese are phosphate‑rich; cutting back on these can lower the dose of binders needed. A simple rule is to eat fresh meats, fruits, and vegetables while limiting processed snack foods. When patients pair a low‑phosphate diet with binders taken at meals, the overall phosphate burden drops dramatically, improving lab numbers and quality of life.

Dosing matters. Binders should be taken with every main meal and snack, exactly as prescribed. Too early or too late dosing reduces effectiveness because phosphate isn’t present in the gut. Some binders require a few minutes of chewing; others can be swallowed whole. Common side effects include constipation, nausea, or a metallic taste, but most resolve with dose adjustment or a switch to a different binder.

Regular lab monitoring guides therapy. Target serum phosphate usually sits between 3.5 and 5.5 mg/dL for dialysis patients, but individual goals may vary. Physicians check phosphate, calcium, and PTH every 1–3 months, tweaking binder type or dose as needed. When phosphate stays high despite maximal binder therapy, a calcimimetic may be added, or a surgical option like parathyroidectomy considered.

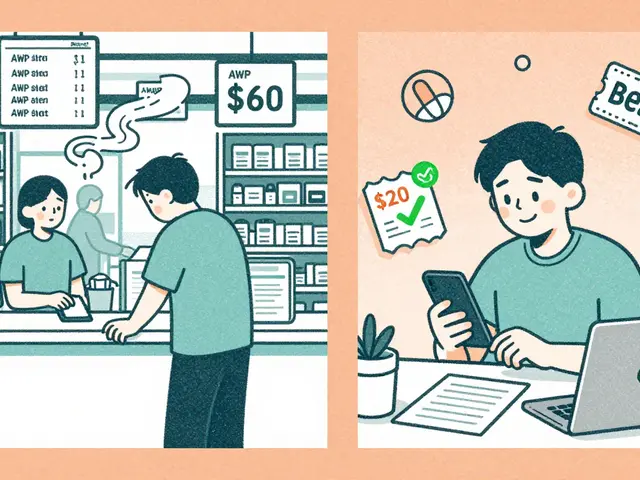

Patient education is a cornerstone of success. Explaining why binders matter, how to take them, and what foods to avoid empowers patients to stick with the regimen. Simple tools—pill organizers, reminders on phone apps, and printed charts—can boost adherence. The next section of our site gathers detailed guides on specific binders, buying options, and tips for safe use, so you can find exactly what you need.