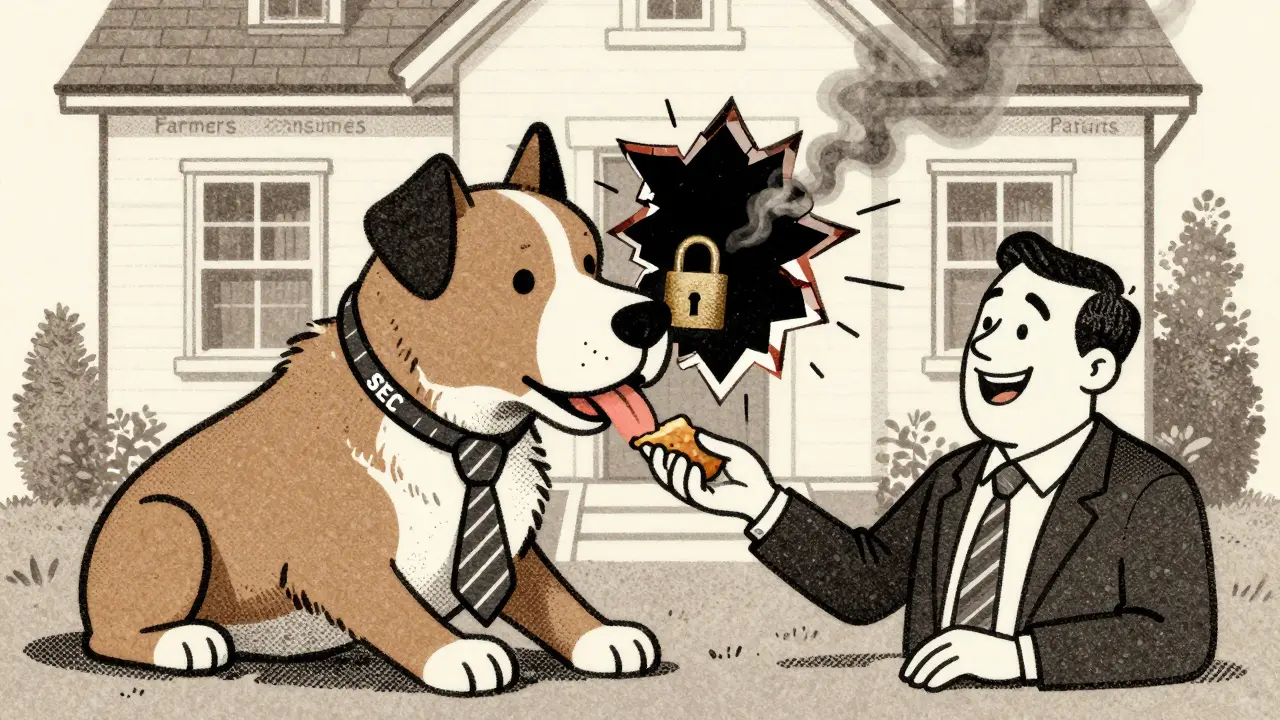

Imagine a watchdog that’s supposed to guard your home, but instead spends its days taking treats from the burglar and ignoring the broken lock. That’s regulatory capture in action. It’s not a conspiracy theory. It’s a well-documented pattern where agencies meant to protect the public end up serving the industries they’re supposed to control.

What Regulatory Capture Really Means

Regulatory capture happens when the companies being regulated start calling the shots. Not through illegal bribes-though that happens too-but through quieter, more systemic ways. Think of it as a slow takeover. Regulators begin to see the world through the eyes of the industries they oversee. They start believing that what’s good for the company is good for everyone. This isn’t new. Back in 1887, the U.S. created the Interstate Commerce Commission to stop railroads from overcharging farmers. By 1900, the same agency was hiking rates at the railroads’ request. The regulators didn’t wake up one day and decide to betray the public. They got used to talking to the same people, hearing the same arguments, working alongside the same executives. Over time, their priorities shifted. Today, it’s happening in finance, energy, pharmaceuticals, and tech. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) had revolving door relationships with 87% of the biggest Wall Street firms before the 2008 crash. That means regulators left to work for the banks they were supposed to police-and the banks hired them back. It’s not corruption. It’s culture.The Two Main Ways Capture Happens

There are two main paths to regulatory capture: materialist and cultural. Materialist capture is about money. It’s the revolving door-officials leaving government jobs to join the industries they regulated, then coming back as lobbyists. Between 2008 and 2018, 53% of senior U.S. Department of Defense officials joined defense contractors within a year of leaving. That’s not coincidence. It’s incentive. Why push for strict rules if your next job depends on being nice to the industry? Then there’s cultural capture. This is subtler. Regulators spend years working with industry experts. They attend the same conferences. They read the same technical reports. They start to trust the industry’s data, even when it’s incomplete. They begin to think, “If these smart engineers say it’s safe, it must be.” The FAA’s handling of the Boeing 737 MAX is a textbook example. Over 96% of safety reviews were delegated to Boeing employees. Regulators didn’t have the time, the staff, or the technical know-how to double-check. So they trusted the maker to police itself. When the planes crashed, it wasn’t because someone took a bribe. It was because the system stopped asking hard questions.Why the Public Doesn’t Fight Back

You might wonder: if this is so obvious, why hasn’t the public stopped it? Because the costs are spread thin, and the benefits are concentrated. Take sugar tariffs in the U.S. Every American household pays about $33 extra per year because the government protects 4,318 domestic sugar producers. That’s $3.9 billion a year in extra costs. But who notices $33? Not most people. Meanwhile, those 4,318 producers gain $1.2 billion in extra profits. They have every reason to lobby hard. They hire lawyers, fund political campaigns, and hire former regulators. Consumer groups? They’re underfunded. Industry groups spend 17 times more per person on lobbying than public interest organizations. That’s not a fair fight. It’s a rigged one.

Real Cases, Real Damage

In the UK, HM Revenue and Customs ran “Project Merlin” from 2012 to 2019. It gave 1,842 multinational corporations secret tax deals-averaging £427 million each-while telling the public corporate tax rates stayed at 19%. The public paid the difference through higher taxes or reduced services. In energy, Ofgem approved £17.8 billion in bill increases between 2015 and 2020 to fund network upgrades. But the energy companies kept profit margins at 11.2%, well above the 6.8% limit. Regulators didn’t push back. Why? Because they trusted the companies’ claims about costs and investments. And in pharma, former EPA officials who left government and joined fossil fuel companies saw a 28-day average delay in enforcement actions during their transition. That’s not a coincidence. That’s a pattern.Why Reform Keeps Failing

There are rules meant to stop this. The U.S. Ethics in Government Act requires a “cooling-off period” before former officials can lobby their old agency. But 41% of violations go unpunished. The EU’s Transparency Register asks lobbyists to disclose their activities. Only 32% of big companies comply. Why? Because the system is designed to be easy to game. Regulators are underfunded. They need industry expertise. They’re isolated from public scrutiny. And politicians don’t want to upset powerful donors. Even well-intentioned fixes fall short. Training programs for regulators help-Canada’s program cut industry meeting times by 27% and boosted public input by 43%. But without real consequences for violations, they’re bandaids on a broken system.

What’s Changing? And What Could Work

There are signs of hope. New Zealand’s independent Regulatory Standards Bill reduced industry-preferred regulations from 68% to 31% between 2016 and 2022. How? By forcing regulators to justify every rule in public, with input from consumers, not just corporations. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission launched its own “Regulatory Capture Initiative” in 2023. It now requires full disclosure of all industry contacts and created a new Office of Regulatory Integrity with a $23 million budget. That’s a start. France’s “Convention Citoyenne pour le Climat” brought together 150 randomly selected citizens to shape climate policy. They cut energy sector influence by 52%. Why? Because ordinary people, not lobbyists, were at the table. The key isn’t more rules. It’s more transparency. More public involvement. More accountability. Regulators need to be answerable to voters, not just CEOs.The Bigger Picture

Regulatory capture isn’t just about unfair prices or unsafe products. It’s about trust. When people believe the system is rigged, they stop believing in democracy. A 2023 Pew survey found 78% of Americans are deeply concerned about industry influence on regulators. That’s not just a statistic. It’s a warning. The World Bank calls regulatory capture a “systemic risk to effective governance” in nearly half the countries it studied. The OECD estimates it costs member nations 0.8% of GDP every year-money lost to inefficiency, overcharging, and wasted resources. And it’s getting worse. The cryptocurrency industry spent $128 million on U.S. lobbying in 2022-a 273% jump since 2020. Regulators are scrambling to understand blockchain, while lobbyists use AI to flood comment systems with 17,000 fake public comments per hour. This isn’t about one agency. It’s about the entire structure of modern governance. When regulators stop serving the public, they become part of the problem.What You Can Do

You might feel powerless. But you’re not. Demand transparency. Ask your representatives: Who funds the regulators? Who sits on advisory panels? Are there public records of industry meetings? Support watchdog groups. Organizations like Public Citizen, the Center for Responsive Politics, and Corporate Europe Observatory track these issues. They need funding and attention. Speak up in public comment periods. Even one voice matters. When regulators hear from real people-not just corporate lawyers-they remember who they work for. Regulatory capture isn’t inevitable. It’s a choice. And choices can be changed.What is regulatory capture?

Regulatory capture occurs when government agencies designed to protect the public end up serving the interests of the industries they regulate. This happens through subtle influence-like revolving doors between industry and government, reliance on industry-provided data, or political pressure-not necessarily through outright bribery.

Is regulatory capture illegal?

Not always. Many forms of capture-like former regulators taking industry jobs or accepting industry input during rulemaking-are legal. What makes it dangerous is that it undermines public trust and distorts policy, even when no laws are broken.

Which industries are most prone to regulatory capture?

Finance, energy, pharmaceuticals, and defense are the most vulnerable. The World Bank found finance has the highest capture rate at 67%, followed by energy at 58%. These industries have high profits, complex regulations, and strong lobbying power.

How does the revolving door contribute to capture?

When regulators leave government to work for the companies they once oversaw, they create a cycle of favoritism. Companies hire them for their inside knowledge, and regulators know that a cozy relationship now could lead to a high-paying job later. Between 1990 and 2020, 92% of former SEC commissioners took jobs with regulated firms within 18 months of leaving office.

Can regulatory capture be reversed?

Yes, but it takes structural change. New Zealand reduced industry influence on regulation by 37% by requiring independent public reviews. France used citizen assemblies to cut energy sector influence by over half. Transparency, public participation, and independent oversight are the keys.

Coy Huffman

February 3, 2026 AT 17:50

this is why i stopped trusting any 'expert' who works for the government. they're all just waiting for their next gig at a corp. 🤷♂️

Amit Jain

February 4, 2026 AT 14:00

in india also same thing. big pharma control health ministry. people suffer but no one talk about it.

Keith Harris

February 6, 2026 AT 00:08

Oh wow. A 10-page essay on how capitalism is evil. Did you also find a unicorn that pays taxes? 🙄 The real problem is that regulators are underpaid, overworked, and surrounded by PhDs who speak fluent 'corporate'. You want change? Pay regulators more than the companies they regulate. But nooo, let’s just cry about it.

Kunal Kaushik

February 6, 2026 AT 13:24

this hit hard. i work in tech and i’ve seen how ‘consultants’ from agencies just nod along with what the big firms say. it’s not malice… it’s just easier to go with the flow. 😔

Prajwal Manjunath Shanthappa

February 8, 2026 AT 03:11

Regulatory capture? Please. This is merely the inevitable consequence of a post-industrial society that has outsourced its moral compass to a cadre of technocratic bureaucrats who, by virtue of their epistemic superiority, are incapable of comprehending the vulgarities of democratic accountability. The public doesn't understand complexity-so they blame the system. Pathetic.

Wendy Lamb

February 8, 2026 AT 15:07

I’ve worked with regulators. They’re not evil. They’re just tired. And when you’re drowning in paperwork and every meeting is with the same 12 lawyers, you start believing their numbers. It’s not corruption-it’s burnout.

Antwonette Robinson

February 9, 2026 AT 10:19

So let me get this straight… the system is broken because people are human? Shocking. Next you’ll tell me water is wet and gravity exists. 😴

Ed Mackey

February 10, 2026 AT 07:07

i read this whole thing and i just… wow. i had no idea it was this bad. i mean, i knew the revolving door was a thing, but 92% of ex-sec commissioners? that’s insane. sorry for the typos, typing on phone 😅

Katherine Urbahn

February 11, 2026 AT 05:46

This is an egregious failure of governance. The erosion of public trust is not merely a political concern-it is a foundational collapse of the social contract. We must institute mandatory recusal protocols, enforce lifetime lobbying bans, and establish independent oversight bodies with prosecutorial authority. Anything less is complicity.

Alex LaVey

February 11, 2026 AT 09:53

I’ve met regulators who truly care. They’re just outnumbered. The real win? When citizens show up to public hearings. Not the lawyers. Not the lobbyists. Real people with real stories. That’s how New Zealand did it. We can too. 💪

Jhoantan Moreira

February 12, 2026 AT 19:44

this is why i moved from the US to the UK. i thought it’d be better here… turns out we’re just better at hiding it. 🇬🇧💔

Justin Fauth

February 13, 2026 AT 20:50

So let me get this straight-you’re mad because American companies are successful? Grow up. If you don’t like the system, move to Venezuela. We built this. You didn’t.

Joy Johnston

February 14, 2026 AT 09:01

The data is irrefutable. Industry lobbying expenditures exceed public interest spending by a factor of seventeen. The structural imbalance is not accidental-it is engineered. The solution requires institutional redesign, not moral appeals.

Shelby Price

February 14, 2026 AT 23:37

i just read this and i’m wondering… how many of these regulators have kids? do they ever think about what kind of world they’re leaving them? 🤔