When you take a pill, you expect it to help. But what if part of what you feel-headache, nausea, fatigue-has nothing to do with the drug itself? What if your brain is making you feel it?

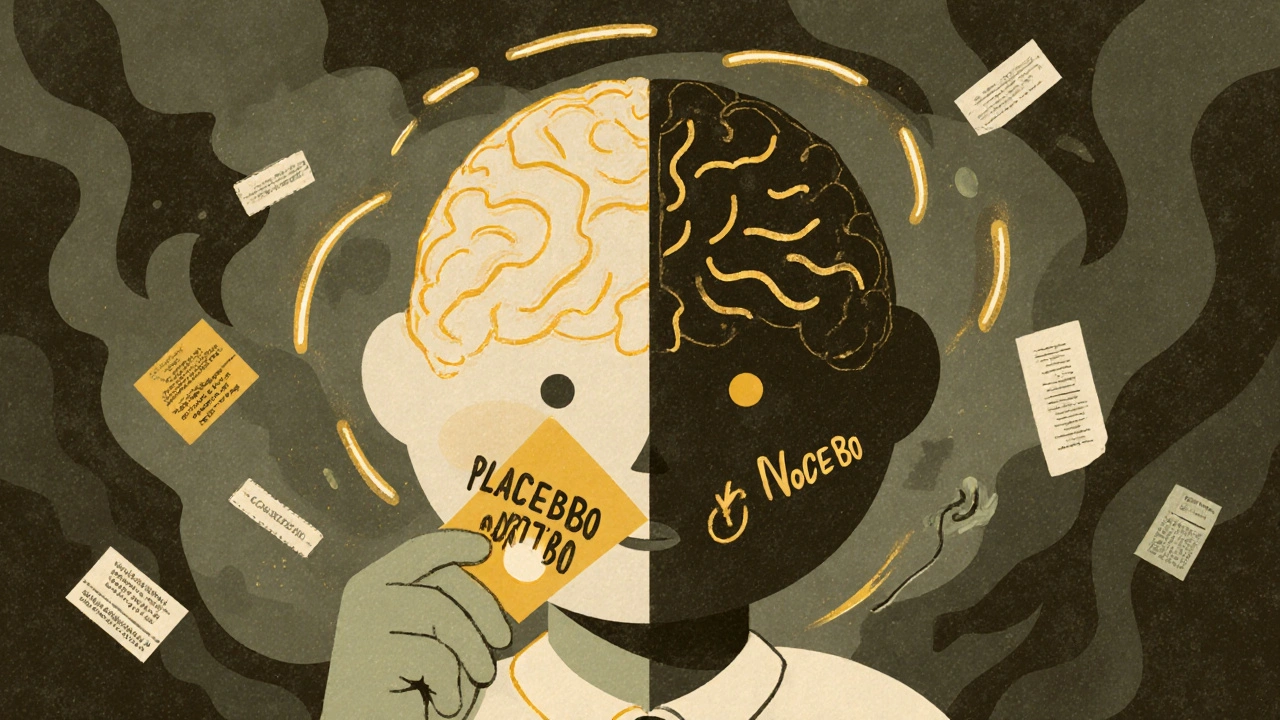

This isn’t science fiction. It’s real. And it’s happening more often than you think. Studies show that up to 76% of side effects reported in clinical trials occur in people who took a sugar pill. Not the real medicine. Just a placebo. That’s the power of expectation. When you believe a treatment will help, you might feel better-even if it’s fake. That’s the placebo effect. But when you expect harm, you might feel worse-even if there’s nothing in the pill to cause it. That’s the nocebo effect.

What Exactly Is a Nocebo Effect?

The word nocebo comes from Latin, meaning “I shall harm.” It was coined in 1961 to describe the dark twin of the placebo effect. While placebos can ease pain or reduce anxiety through positive belief, nocebos trigger real physical symptoms because of fear, warning labels, or bad stories.

Think about this: You’re prescribed a new migraine medication. The leaflet says: “Common side effects include dizziness, nausea, and fatigue.” You read it. You worry. The next day, you take the pill. Within hours, you feel dizzy. Your stomach churns. You’re tired. You call your doctor. You think the drug is messing with you. But here’s the twist: In clinical trials, people taking a placebo pill-no active ingredient-reported the exact same symptoms at nearly the same rates. The drug didn’t cause it. Your expectation did.

Research from the University of Maryland and Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich shows that 70-80% of nocebo responses come from what doctors and pamphlets say. Hearing “this might make you sick” is enough to make you sick-even if nothing is in the pill.

How the Brain Turns Worry Into Physical Pain

Your brain isn’t just imagining this. It’s real. Brain scans show that when someone expects a side effect, areas like the anterior cingulate cortex and insula light up. These are the same regions that process pain and stress. The brain doesn’t care if the threat is real-it reacts to the belief.

When you expect nausea, your body releases cortisol. Your heart rate ticks up. Your gut slows down. Your immune system shifts. In one study, people given a placebo pill and told it might cause headaches showed measurable increases in brain activity linked to pain perception. Their bodies were responding to a message, not a chemical.

This isn’t just about pain. In COVID-19 vaccine trials, 76% of people who got a saline injection (no vaccine) reported headaches or fatigue-symptoms they’d been told were common. These weren’t random. They matched the side effects described in the consent forms. The body was reacting to words, not antigens.

Placebo vs Nocebo: The Numbers Don’t Lie

Let’s compare what the data says:

| Condition | Placebo Effect Rate | Nocebo Effect Rate | Key Symptoms Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migraine | 30-50% improvement | 20-30% reporting side effects | Headache, nausea, dizziness |

| Antidepressants | 25-40% mood improvement | 25-35% reporting fatigue, nausea | Weight gain, sexual dysfunction |

| Anticonvulsants | 20-35% reduction in seizures | 12-15% reporting memory issues | Memory lapses, tingling, dry mouth |

| Chronic Pain | 35-55% pain reduction | 30-40% reporting increased pain | Back pain, muscle tightness |

| COVID-19 Vaccines | Not applicable | 76% of placebo group reported fatigue/headache | Fatigue, headache, fever |

Notice something? The nocebo effect isn’t just common-it’s often stronger and lasts longer. A 2025 study in eLife Sciences found that negative expectations didn’t fade over time like positive ones. If you expect to feel sick on day one, you’re likely to feel sick on day eight. But if you expect to feel better? That boost fades after a few days.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

This isn’t just academic. It’s costing lives and money.

One in four patients stops taking their medication because they think they’re having side effects-side effects that were never caused by the drug. In Australia, the U.S., and Europe, up to 20% of doctor visits for “side effects” turn out to be nocebo reactions. Patients take extra pills to fight nausea from a drug that didn’t cause it. They skip doses. They avoid treatment altogether.

The financial impact? Over $1.2 billion a year in the U.S. alone-on unnecessary tests, ER visits, and extra prescriptions. That’s not just waste. It’s harm.

And it’s not just patients. Doctors are caught in the middle. They’re trained to warn about risks. But when every warning triggers more symptoms, they’re stuck between honesty and harm.

How Doctors Are Fighting Back

Some are changing how they talk.

Instead of saying, “3% of patients get nausea,” they say, “Out of 100 people, 3 might feel a little queasy.” That simple shift reduces nocebo responses by 15-25%, according to studies by Dr. Luana Colloca.

Some clinics now use “expectation reframing.” A doctor might say: “Most people feel better within a week. A few might feel a bit tired at first-but that usually passes, and it’s a sign your body is adjusting, not reacting badly.”

There’s also “open-label placebo”-giving patients a sugar pill and telling them outright: “This has no active ingredient, but studies show it can still help your symptoms.” In trials for IBS and chronic pain, this approach improved symptoms by 25-35%. You don’t need to lie to get results.

Electronic health records now flag patients at higher risk: those with anxiety, past negative experiences with meds, or a tendency to catastrophize. These patients get tailored conversations-not just leaflets.

What You Can Do If You’re Worried About Side Effects

If you’re starting a new medication and you’re scared:

- Ask your doctor: “What percentage of people actually stop because of side effects?” Not just “What are the side effects?”

- Don’t read the leaflet before taking the pill. Read it after-if you need to. First impressions matter.

- Keep a symptom journal. Note when symptoms start. Did they begin before or after you read about them?

- If you feel something, don’t assume it’s the drug. Ask: “Could this be my brain reacting to what I’ve heard?”

- Don’t stop cold. Talk to your doctor. Many side effects fade in a week or two. Stopping too soon means you lose the chance to benefit.

And if you’ve had a bad reaction before? That’s not just bad luck. It’s a signal. Your brain learned to expect harm. But it can learn differently, too.

The Bigger Picture

The nocebo effect isn’t about weakness. It’s about how human minds work. We’re wired to anticipate danger. That kept our ancestors alive. But in modern medicine, that same wiring can turn harmless pills into villains.

Pharmaceutical companies are now spending $50-75 million per drug just to design patient information that doesn’t trigger nocebo responses. The FDA and EMA now require analysis of placebo-group side effects in drug approvals. AI tools are being tested to predict who’s most likely to have nocebo reactions-based on speech patterns, past medical history, and even word choice.

One day, doctors might say: “Your brain is sensitive to negative suggestions. We’ll adjust how we talk about this drug.” That’s not magic. It’s medicine catching up with the mind.

Medication side effects aren’t always in the pill. Sometimes, they’re in the message.

Can placebo pills really make people feel better?

Yes. Studies show that placebo pills can reduce pain, anxiety, and fatigue by 30-60% in conditions like migraines, depression, and chronic pain. The improvement isn’t imaginary-it’s measurable in brain activity and hormone levels. The mind triggers real biological changes when it expects relief.

Are nocebo effects real or just in people’s heads?

Nocebo effects are real physiological responses. They cause measurable changes in cortisol, heart rate, and brain activity. People don’t just think they feel worse-they actually experience physical symptoms like nausea, headaches, and fatigue. The body responds to expectation as if it were a chemical trigger.

Why do some people get nocebo effects and others don’t?

People with anxiety, past negative medical experiences, or a tendency to catastrophize are 2-3 times more likely to experience nocebo effects. Genetics also play a role-some people have variations in the COMT gene that make them more sensitive to negative expectations. But anyone can be affected if the warning is strong enough.

Can reading medication leaflets cause side effects?

Yes. Studies show that reading detailed side effect lists increases the likelihood of experiencing those symptoms-even if you’re taking a placebo. The more specific the warning, the higher the chance of a nocebo reaction. That’s why some doctors now recommend reading the leaflet only after starting the medication.

Is it ethical to downplay side effects to avoid nocebo effects?

It’s not about hiding risks-it’s about how you communicate them. Ethical guidelines now support using absolute numbers (“3 in 100”) instead of percentages (“3%”), focusing on what most people feel, and framing side effects as temporary adjustments. Transparency without fear-mongering is the goal.

Can open-label placebos work even if you know they’re fake?

Yes. In trials for IBS and chronic pain, patients given sugar pills and told, “This is inert but can still help,” reported 25-35% symptom improvement. The brain responds to the ritual of treatment-even without deception. This challenges the old idea that placebo effects require lying.

What’s Next?

The future of medicine isn’t just about better drugs. It’s about smarter communication. As AI tools learn to spot who’s at risk for nocebo reactions, and as doctors are trained to speak in ways that reduce fear, we might stop blaming pills for problems they didn’t cause.

Medication side effects aren’t always in the bottle. Sometimes, they’re in the way we talk about them.

Cecil Mays

October 29, 2025 AT 09:08

This is wild! I had no idea my brain could trick me into feeling sick just from reading a leaflet 😱 I just started a new med and skipped the pamphlet on purpose. Best decision ever. Thanks for the eye-opener!

Sage Druce

October 30, 2025 AT 00:59

The nocebo effect is one of the most powerful forces in modern medicine and nobody talks about it enough. Your brain is not just a passive observer-it’s an active participant in your healing or harm. This isn’t psychology fluff, it’s biology with consequences. If we trained doctors to speak like healers instead of lawyers, we’d save billions and lives. Period.

Tanuja Santhanakrishnan

October 31, 2025 AT 07:47

As someone from India who’s seen grandparents refuse life-saving meds because of horror stories from neighbors, this hits home. We don’t need more warnings-we need storytelling that heals, not frightens. My aunt took her BP pill for years without reading the leaflet and felt fine. Then she read it, panicked, and stopped. Two weeks later she was in the hospital. The pill didn’t hurt her-fear did.

Raj Modi

November 2, 2025 AT 03:04

While the data presented here is compelling and aligns with meta-analyses from the Lancet and JAMA on expectation-driven somatic responses, one must contextualize the nocebo phenomenon within the broader epistemological framework of biopsychosocial medicine. The activation of the anterior cingulate cortex and insula during nocebo induction suggests a neurophysiological substrate that is not merely psychological but ontologically real-meaning that the perception of threat, even when unfounded, triggers autonomic and endocrine cascades indistinguishable from those elicited by pharmacological agents. This necessitates a paradigm shift in informed consent protocols, wherein the framing of adverse event probabilities must be calibrated not merely for transparency but for neurocognitive resilience.

Stuart Palley

November 2, 2025 AT 03:20

Of course it’s all in your head. People are just weak. If you can’t handle a little side effect warning, maybe you shouldn’t be taking medicine at all. I’ve read every leaflet and never felt a thing. You’re just letting your mind control you. Stop being so dramatic.

Natalie Eippert

November 2, 2025 AT 19:58

Who funded this article? Big Pharma? Because they’re the ones who profit when people stop taking meds. You’re telling us to ignore the warnings? That’s how people die. You think your brain is so smart? It’s not. It’s being manipulated. The government and drug companies don’t want you to know how dangerous these pills really are.

kendall miles

November 4, 2025 AT 16:20

Wait… so you’re saying the government and pharma are using side effect lists as psychological weapons to make people sick? That’s not coincidence. That’s a controlled experiment. They’ve been doing this since the 1970s. The WHO knows. The FDA knows. They’re testing mass nocebo conditioning on the population. Look at the COVID vaccine trials-76% of placebo people got headaches? That’s not random. That’s programming. You’re being conditioned. Wake up.

STEVEN SHELLEY

November 5, 2025 AT 01:24

you guys are missing the point. the real truth is that the placebo/nocebo thing is just a distraction. the real problem is that the pills are laced with microchips that track your brainwaves and feed back into the system. the side effects? theyre not from the drug, theyre from the signal. the leaflets? theyre just to make you think its your fault. i read the studies and they dont mention the 5g interference. ask yourself why the FDA never talks about that. they dont want you to know. im not crazy. im just the only one who looked

Gary Fitsimmons

November 5, 2025 AT 02:22

I’ve been a nurse for 20 years and this is 100% real. I’ve seen patients cry because they thought the medicine was making them sick… then we told them it was a sugar pill and they felt better in minutes. It’s not about being weak. It’s about how we talk to people. A little kindness and clarity goes further than a 10-page warning sheet.

Karen Werling

November 5, 2025 AT 20:28

I love how this article doesn’t blame people for feeling scared. We’re taught to fear medicine from day one-TV ads, scary pamphlets, doctors rushing through explanations. It’s not just the pills, it’s the whole system. I gave my mom an open-label placebo for her back pain last year. Told her it was inert. She said it helped more than the real one. She cried. Not because she was fooled… because she finally felt heard.

Sarah Schmidt

November 6, 2025 AT 08:24

The nocebo effect is not merely a neurological quirk-it is a mirror held up to the epistemological crisis of modern healthcare. When we reduce human suffering to chemical interactions, we erase the ontological weight of belief, narrative, and cultural context. The body does not respond to molecules alone; it responds to stories. And the story we tell about medication is one of dread, of impending doom, of inevitable decay. This is not a failure of pharmacology-it is a failure of hermeneutics. We have forgotten how to speak healing words.

Lorena Cabal Lopez

November 7, 2025 AT 14:43

So what? People are just too sensitive. If you can’t handle a little nausea, maybe you shouldn’t be on meds. This whole thing feels like excuse-making. I’ve been on 12 different prescriptions and never had a problem. Maybe you just need to toughen up.

Glenda Walsh

November 7, 2025 AT 22:01

Wait, so… you’re saying if I don’t read the leaflet, I won’t get side effects? But what if I accidentally see one? Like on a website? Or in a YouTube video? Or if my friend tells me? What if I dream about it? What if my dog barks when I take the pill? Is that a nocebo too? I’m so confused now. I think I’m already feeling the side effects just from reading this. I need to lie down. And maybe call a doctor. Or a therapist. Or both. Please help.

Billy Gambino

November 9, 2025 AT 21:57

The paradox is not in the pill, but in the covenant between physician and patient. The nocebo effect reveals the inherent contradiction of modern medical discourse: we demand transparency, yet transparency breeds iatrogenesis. The truth, in its raw form, becomes a toxin. The placebo, in its deceptive simplicity, becomes a balm. This is not a failure of science-it is the collapse of epistemic authority. We no longer believe in the healer, only in the mechanism. And so, the mechanism, stripped of ritual, of trust, of sacred silence, becomes a weapon against itself.