When you take opioids for pain, you might expect relief - not a sinking feeling. But for many people, the very drugs meant to ease physical suffering can quietly drag down their mood. It’s not just stress or bad days. This is real, measurable depression - and it’s more common than most doctors admit.

Why Opioids Can Make You Feel Worse

Opioids don’t just block pain signals. They interact with the brain’s natural reward and emotion systems. In the short term, that can feel like relief - even a lift. But over weeks or months, your brain adapts. The same receptors that once helped you feel calm start to misfire. Your body produces less of its own natural painkillers and mood boosters. That’s when low energy, loss of interest, and emotional numbness creep in. Studies show that between 30% and 54% of people with chronic pain also have major depression. But here’s the catch: many of those cases aren’t diagnosed. General practitioners miss about half of depression cases in patients on long-term opioids. So someone might be told, “Your pain is getting worse,” when really, their mood is collapsing beneath the weight of the medication. A 2020 genetics study in JAMA Psychiatry found something alarming: people with a genetic tendency to use prescription opioids were more likely to develop major depressive disorder. That’s not just correlation - it suggests opioids themselves may increase depression risk. The higher the dose, the worse it gets. People taking more than 50 mg of morphine equivalent per day were over three times more likely to develop depression than those not using opioids at all.The Two-Way Street Between Pain and Mood

It’s not just opioids causing depression - depression can also push people toward opioids. People with untreated depression often report pain more intensely. They’re more likely to seek out pain meds, and more likely to keep using them longer. One study found depressed patients were twice as likely to transition from short-term to long-term opioid use. This creates a loop: pain leads to opioid use, opioid use worsens depression, depression makes pain feel worse, so you take more opioids. It’s hard to break. And it’s why simply increasing your pain medication often makes things worse - not better. The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that people with major depressive disorder are 2.5 times more likely to develop an opioid use disorder. That’s not coincidence. It’s biology. The brain’s reward system gets tangled up in both conditions.What to Look For: Signs of Opioid-Induced Depression

You don’t need to feel suicidal to be depressed. With opioids, mood changes can be subtle. Watch for:- Loss of interest in things you used to enjoy - hobbies, friends, even food

- Feeling emotionally flat or numb, even when good things happen

- Constant fatigue, even after sleeping

- Difficulty concentrating or making simple decisions

- Sleeping too much or too little - and not because of pain

- Feeling hopeless or worthless, even if your pain is under control

Monitoring Is Not Optional - It’s Essential

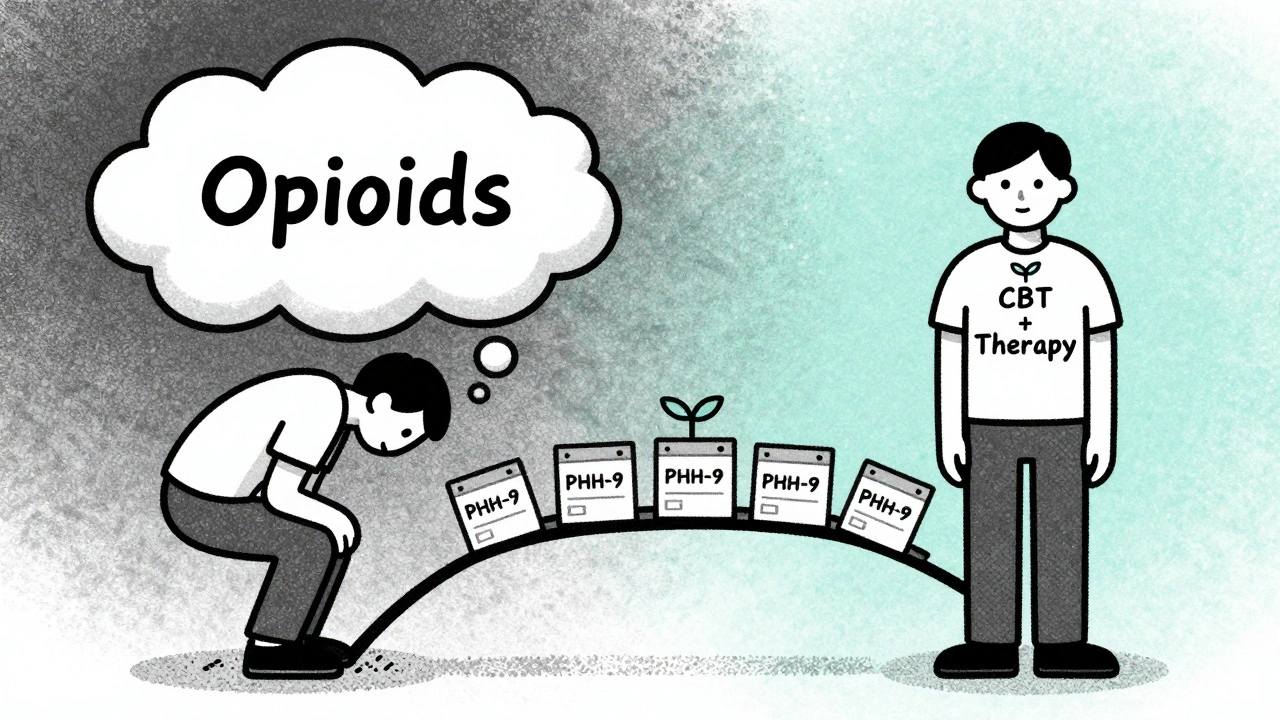

The CDC says doctors should check for depression before starting opioids and regularly after. But in 2020, only 39% of primary care doctors did this consistently. That’s a dangerous gap. The simplest tool is the PHQ-9 - a nine-question screen that takes less than five minutes. It asks about sleep, energy, appetite, concentration, and feelings of hopelessness. A score of 10 or higher suggests moderate to severe depression. Many clinics use it at the first visit, then every three months. But if you’re on high-dose opioids or have a history of depression, monthly checks are better. Dr. Roger Weiss, who led a major trial on opioid treatment, recommends monthly screening for the first six months. His team found that nearly 3 in 10 patients developed or worsened depression within three months of starting long-term opioid therapy. That’s fast. And it’s preventable.Can Opioids Actually Help Depression?

This is where it gets confusing. In lab studies, opioids like morphine and buprenorphine reduce signs of depression in animals. In humans, low-dose buprenorphine (1-2 mg daily) has shown antidepressant effects in people who didn’t respond to regular antidepressants. One study showed 47% of treatment-resistant depression patients improved within four weeks. So why the contradiction? Because context matters. Short-term use, especially in acute pain, can lift mood by reducing suffering. But long-term, high-dose use rewires the brain. It’s like drinking coffee to stay awake - at first it helps. After months, you need more just to feel normal. And when you stop, you crash. Buprenorphine is approved for opioid addiction, not depression. That means doctors can’t legally prescribe it just for mood - even if it works. It’s a frustrating gap in care.

What Works: Breaking the Cycle

The best way out isn’t stopping opioids cold - it’s treating both pain and mood at the same time. In the COMBINE trial, patients who got cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) along with pain management reduced their opioid doses by 32% - without worsening pain. CBT helps reframe how you think about pain and emotions. It teaches coping skills that reduce reliance on pills. Antidepressants like SSRIs (sertraline, escitalopram) can help too, especially when paired with therapy. But they take weeks to work. That’s why combining them with behavioral support is key. Some patients benefit from tapering opioids slowly while increasing non-opioid pain treatments - physical therapy, acupuncture, nerve blocks, or even mindfulness. One study showed that when depression improved, pain perception dropped, even without changing opioid doses.What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re on opioids and feeling off:- Take the PHQ-9 test online - it’s free and confidential. Many health sites offer it.

- Write down your mood changes: when they started, what triggers them, how they affect your daily life.

- Ask your doctor: “Could my opioids be making my mood worse?” Don’t wait for them to ask.

- Request a referral to a pain psychologist or psychiatrist who understands opioid-related depression.

- Don’t stop opioids on your own. Sudden withdrawal can make depression worse.

The Future Is Integrated Care

New research is underway to untangle the brain mechanisms behind opioid-induced depression. Columbia University is using brain scans to see how opioid use changes mood circuits. A five-year study tracking 5,000 chronic pain patients will map how mood shifts over time. The goal? To build treatment models that treat pain and depression as one problem - not two separate ones. That means doctors who specialize in pain working side-by-side with mental health providers. It means insurance covering therapy as part of pain care. It means patients being asked about their mood - not just their pain level. Until then, you have power. You can ask for screening. You can track your symptoms. You can insist on a plan that doesn’t just numb your pain - but helps you feel like yourself again.Can opioids cause depression even if I’m taking them as prescribed?

Yes. Even when taken exactly as directed, long-term opioid use can change brain chemistry in ways that increase depression risk. Studies show people on daily opioids for more than a few months are significantly more likely to develop depressive symptoms - regardless of whether they have a prior history of mental health issues.

How long does it take for opioids to affect my mood?

Mood changes can start within weeks. In one study, nearly 30% of patients on long-term opioids developed new or worsening depression within three months. The risk increases with higher doses and longer use. Don’t wait for severe symptoms - early signs like losing interest in things you enjoy are red flags.

Should I stop taking opioids if I feel depressed?

No - not without medical supervision. Stopping abruptly can cause withdrawal, which mimics and worsens depression. Instead, talk to your doctor about a plan. Often, slowly reducing the dose while adding depression treatment (like therapy or medication) leads to better outcomes than stopping cold.

Is buprenorphine a good treatment for depression caused by opioids?

Low-dose buprenorphine (1-2 mg daily) has shown antidepressant effects in studies, especially for people who haven’t responded to standard antidepressants. But it’s not FDA-approved for depression, so doctors can’t prescribe it solely for that purpose. It’s most commonly used for opioid addiction - but if you’re on it for addiction and feel better emotionally, that’s a sign it may help your mood too.

What’s the best way to monitor my mood while on opioids?

Use the PHQ-9 questionnaire every month for the first six months, then every three months. It’s free, quick, and validated. Write down how you’ve been feeling - sleep, energy, interest in life, hopelessness - and bring it to your appointments. If your score is 10 or higher, ask for a referral to a mental health professional. Don’t rely on your doctor to notice - be proactive.

Arun Kumar Raut

December 9, 2025 AT 05:16

Been on opioids for lower back pain for 2 years now. Didn't realize my lack of interest in cooking, music, and even hanging with my kids was from the meds. I thought I was just getting old. This post hit hard. Took the PHQ-9 last night - scored 12. Going to talk to my doctor tomorrow. No shame in this. We just need better care.

Thanks for writing this.

Carina M

December 10, 2025 AT 03:49

It is truly lamentable that the medical establishment continues to treat pain and mood as discrete entities, rather than acknowledging the neurobiological interplay that has been empirically validated for decades. The prescribing practices you describe reflect a systemic failure of clinical governance and pharmacological literacy. One must question the integrity of a profession that prioritizes symptom suppression over holistic restoration.

Tejas Bubane

December 11, 2025 AT 15:45

So let me get this straight - you’re saying taking painkillers makes you sad? Wow. Groundbreaking. Next you’ll tell me drinking too much soda causes cavities. Everyone knows opioids are addictive and make you feel like a zombie. The real problem is people who don’t want to deal with their pain and just want a magic pill. Stop blaming the medicine and start blaming the mindset.

Ajit Kumar Singh

December 12, 2025 AT 23:43

India we have same problem people take painkillers for everything even for headache and then they cry why they feel empty no one tells them this is not normal everyone thinks its normal to feel nothing after pills but its not its brain damage its not your fault its the system that sold you this lie

My uncle took tramadol for 5 years now he cant wake up in morning he dont laugh anymore he just stares at wall

Doctors dont care they just give more pills

Sabrina Thurn

December 14, 2025 AT 00:49

It's critical to distinguish between opioid-induced depressive symptoms and comorbid major depressive disorder - the pathophysiology differs significantly. The downregulation of mu-opioid receptors and subsequent dysregulation of the HPA axis and monoaminergic systems underlies the neurochemical shift. Clinically, this manifests as anhedonia and psychomotor retardation, often preceding diagnostic thresholds for MDD. Early intervention with SSRIs or SNRIs, coupled with non-pharmacological modalities like CBT-I, has demonstrated efficacy in mitigating this iatrogenic effect.

iswarya bala

December 15, 2025 AT 08:58

i just started taking oxycodone for my sciatica and lately i’ve been crying for no reason and i dont wanna do anything not even scroll instagram which is like my whole life 😭 i thought i was just lazy but now i think its the meds… i took the phq-9 and got 11… im scared to tell my dr but i think i need to… thank u for this post i dont feel alone anymore

Philippa Barraclough

December 16, 2025 AT 18:23

The longitudinal data presented here, particularly the 2020 JAMA Psychiatry genetic study, raises compelling questions regarding pleiotropic effects of opioid receptor polymorphisms on mood regulation pathways. It is noteworthy that the heritability estimates for opioid use disorder and major depressive disorder demonstrate significant genetic overlap, particularly in regions associated with dopamine transporter function and serotonin reuptake efficiency. This suggests a potential endophenotype that predisposes individuals to both conditions, which may explain the high comorbidity rates observed clinically. Further research into epigenetic modulation of these pathways under chronic opioid exposure is warranted.

Tim Tinh

December 16, 2025 AT 20:41

my cousin was on hydrocodone for a year after surgery and he went from being the life of the party to just sitting on the couch staring at nothing. we thought he was depressed because of the injury - turns out it was the pills. he got off them slow with a pain doc and started therapy. now he’s back to playing guitar and laughing again. it’s not easy but it’s possible. don’t give up.

also - yes, the phq-9 is free. just google it. no login needed.

Tiffany Sowby

December 18, 2025 AT 11:33

Of course opioids cause depression. It’s the same reason people in America get addicted to everything - we don’t want to feel anything. We don’t want to sit with our pain, our grief, our loneliness. So we pop a pill. Then we wonder why we feel worse. This isn’t a medical crisis - it’s a cultural one. We’ve turned our bodies into machines that need constant fixing, not healing.

Brianna Black

December 20, 2025 AT 02:17

THIS. IS. A. SCANDAL.

Doctors are prescribing these drugs like candy. Patients are being left to rot in emotional numbness while insurance refuses to cover therapy. And the pharmaceutical companies? They’re laughing all the way to the bank. I’ve seen it firsthand - my sister was on 80mg morphine daily for three years. She lost her job, her friends, her joy. And when she asked for help? They told her to increase the dose. This isn’t medicine. This is exploitation.

Stacy Tolbert

December 21, 2025 AT 20:04

I’m on 30mg oxycodone a day and I’ve been feeling this way for months. I thought I was just being dramatic. I don’t cry anymore. I don’t laugh. I just… exist. I didn’t know it could be the meds. I’m going to print out the PHQ-9 and take it tonight. I’m scared but I need to do something. Thank you for saying this out loud.

Ronald Ezamaru

December 23, 2025 AT 10:05

For anyone reading this - if you’re on long-term opioids and feel emotionally flat, don’t wait until you’re in crisis. Talk to a pain specialist or a psychiatrist who knows about opioid-induced depression. It’s not weakness. It’s biology. And it’s treatable. I’ve helped dozens of patients reverse this. You’re not alone.

Ryan Brady

December 25, 2025 AT 07:16

LOL. So now we’re blaming the pills? What’s next? Blaming the sun for making you tan? If you’re depressed, go see a shrink. Don’t blame the medicine. People have been taking painkillers for centuries. You think this is new? Grow up.

Raja Herbal

December 26, 2025 AT 00:51

Wow. So opioids make you sad? Who would’ve thought? Next you’ll tell me breathing air causes oxygen toxicity. I’m sure the pharmaceutical reps are sobbing in their boardrooms right now. Meanwhile, real people are in real pain and need relief. Maybe stop trying to pathologize every side effect and just give people the meds they need. Some of us don’t have the luxury of therapy.

Lauren Dare

December 27, 2025 AT 13:22

It’s fascinating how the medical community continues to pathologize patient behavior while ignoring systemic failures. The PHQ-9 is a useful tool, yes - but it’s being deployed as a Band-Aid on a hemorrhaging wound. If 61% of primary care physicians aren’t screening for depression in opioid-treated patients, the problem isn’t patient awareness - it’s institutional neglect. We’ve outsourced mental health to a 9-item questionnaire while underfunding integrated care models by 87%. The solution isn’t more screening - it’s more funding, more training, and more accountability.