When you hear the word biosimilar, you might think it’s just a cheaper version of a brand-name drug-like a generic pill. But monoclonal antibody biosimilars aren’t like that. They’re not copies in the way aspirin is a copy of aspirin. These are complex, living medicines made from living cells, and getting them right takes years of science, testing, and precision. Unlike small-molecule generics, which are chemically identical to their originals, biosimilars are highly similar-not identical-because the molecules are too big and too delicate to replicate perfectly. A monoclonal antibody can weigh 150,000 daltons. That’s more than 25 times heavier than insulin. Even tiny changes in how it’s made-like how sugars are attached to it-can affect how the body reacts. So, the FDA and EMA don’t just approve them because they look alike. They require proof that there are no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, or how well they work.

How Biosimilars Are Different from Generics

Think of a generic drug like a photocopy of a printed page. The ink, the paper, the font-all the same. Now imagine trying to make an exact copy of a snowflake using a 3D printer. Even with the same blueprint, no two will be identical. That’s the difference. Generics are made from chemicals in a lab. Biosimilars are grown in living cell cultures, like tiny biological factories. Every batch has slight variations, just like no two humans are exactly alike. That’s why regulators don’t call them “equivalent.” They call them “similar.” And they demand more than just lab tests. They require clinical trials to prove the biosimilar works the same way in real patients.

The first monoclonal antibody biosimilar approved anywhere was a version of infliximab, sold under the brand name Remicade. It hit the EU market in 2013. The U.S. followed later, with Zarxio (a biosimilar to filgrastim) approved in 2015. But it wasn’t until 2017 that the first biosimilar for a cancer drug-bevacizumab-got the green light in the U.S. Since then, the number has exploded. Today, there are more than 20 approved monoclonal antibody biosimilars in the U.S. alone, and the pipeline is packed with more.

Key Examples and What They Treat

Not all biosimilars are the same. Each one is tied to a specific reference drug and used for a specific disease. Here are the most common ones and what they’re used for:

- Bevacizumab biosimilars (like Mvasi, Zirabev, Vegzelma): Used for colorectal cancer, lung cancer, glioblastoma, and ovarian cancer. Six different versions are approved in the U.S. as of 2023. They block a protein that tumors need to grow blood vessels.

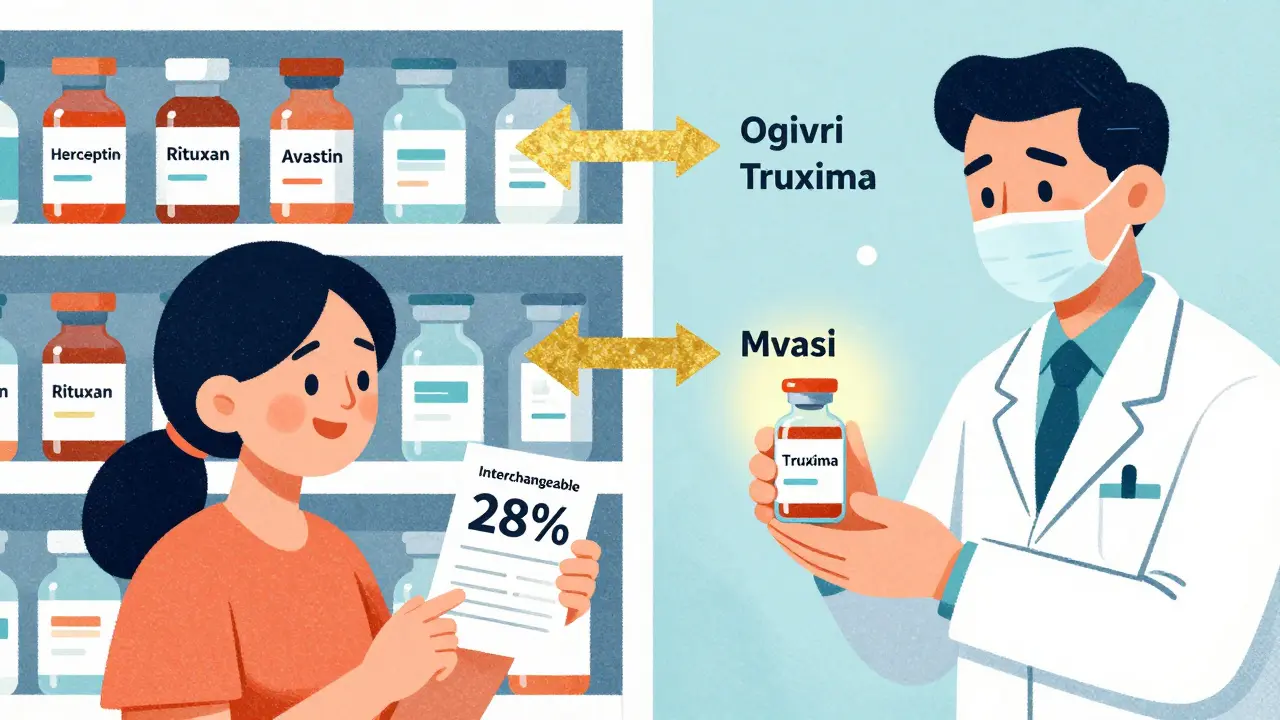

- Rituximab biosimilars (Truxima, Ruxience, Riabni): Used for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and rheumatoid arthritis. These target a protein on immune cells that’s overactive in these diseases.

- Trastuzumab biosimilars (Ogivri, Herzuma, Ontruzant, Trazimera, Kanjinti, Hercessi): Used for HER2-positive breast cancer and stomach cancer. These drugs latch onto HER2 receptors on cancer cells and stop them from multiplying.

- Adalimumab biosimilars (like Hyrimoz): Used for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, Crohn’s disease, and other autoimmune conditions. The first U.S. biosimilar for Humira was approved in late 2023, opening the door for major cost savings.

These aren’t just theoretical. In real-world use, switching from the original drug to a biosimilar has been studied in thousands of patients. A 2022 study in JAMA Oncology tracked 1,247 patients at 15 cancer centers who switched from rituximab to Truxima. No increase in side effects. No drop in effectiveness. And the cost dropped by 28% per treatment cycle. That’s not a small change-it’s life-altering for patients and healthcare systems.

Why Cost Matters So Much

Monoclonal antibody drugs are expensive. A single dose of Herceptin or Keytruda can cost over $10,000. A full course of treatment? Often more than $100,000. Biosimilars don’t bring the price down to generic levels-because the manufacturing is still complex-but they do cut costs by 15% to 35%. And that adds up fast. Evaluate Pharma predicts biosimilar monoclonal antibodies will save the U.S. healthcare system $250 billion between 2023 and 2028. Bevacizumab, trastuzumab, and rituximab biosimilars alone will account for 78% of those savings.

That’s not just about hospitals saving money. It’s about patients being able to afford treatment. It’s about insurance companies covering more people. It’s about making life-saving therapies accessible outside of wealthy countries or private clinics.

Interchangeable Biosimilars: The Next Step

Not all biosimilars are created equal in terms of switching. Most require a doctor’s decision to switch from the original. But some are now labeled “interchangeable.” That means pharmacists can swap them for the brand-name drug without asking the doctor-just like with generics. The first monoclonal antibody biosimilar to get this designation was Remsima (infliximab), approved by the FDA in July 2023. This is a big deal. It removes barriers in pharmacies and makes switching smoother, faster, and more widespread.

But it’s not simple. To get interchangeable status, manufacturers must prove that switching back and forth between the biosimilar and the original doesn’t increase risks. That means multiple studies showing no immune reactions, no loss of effectiveness, and no safety spikes over time. It’s the gold standard of biosimilar science.

Challenges Still in the Way

Despite the progress, adoption isn’t universal. A 2022 survey by the American Society of Clinical Oncology found that only 58% of oncologists felt “very confident” prescribing biosimilars. Many worry about subtle immune reactions, especially with antibodies that target immune cells. There have been rare cases of unexpected allergic responses-like with cetuximab, where some patients had pre-existing antibodies to a sugar molecule (alpha-1,3-galactose) that caused anaphylaxis. While the rate of these events in biosimilars is the same as in the original drugs (about 0.001% of patient-years), fear still lingers.

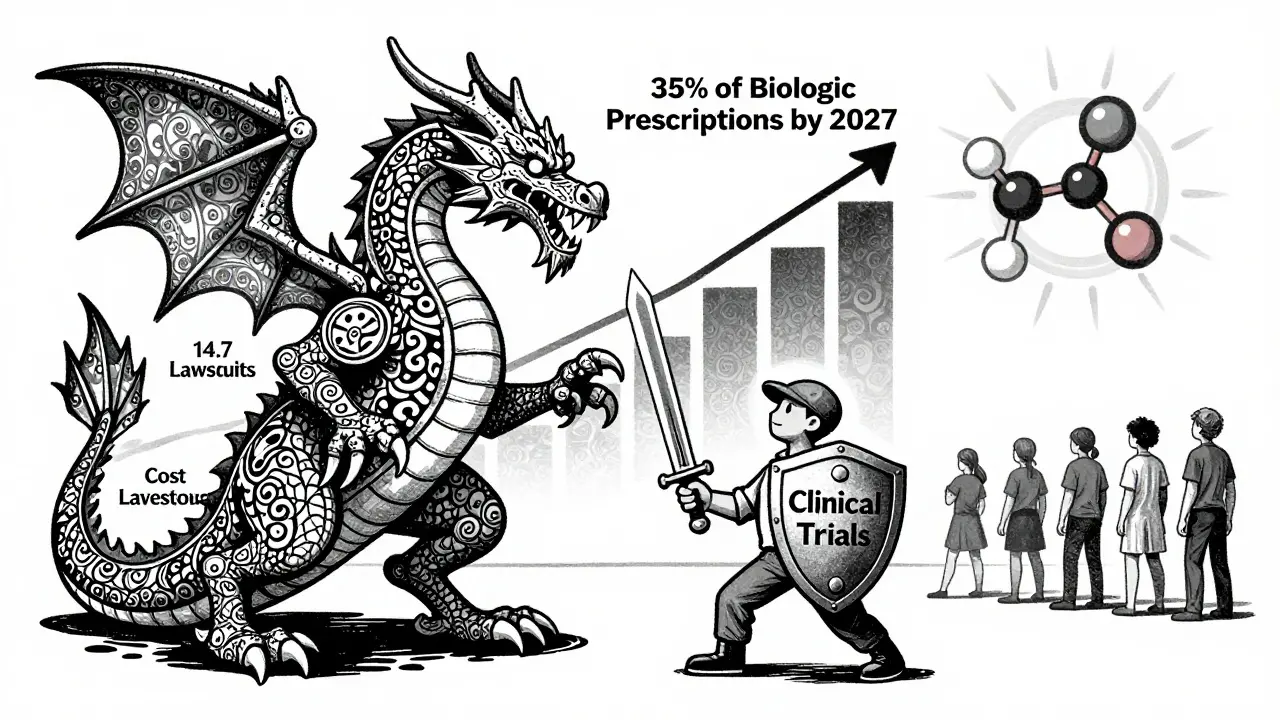

Patent lawsuits are another hurdle. On average, each monoclonal antibody biosimilar faces 14.7 patent challenges before it can launch. These legal battles can delay entry for years, even after regulatory approval. Pharmacy benefit managers also play a role-32% of biosimilar launches in 2023 were blocked from formularies because insurers didn’t include them.

What’s Coming Next

The pipeline is full. As of late 2023, the FDA had 37 monoclonal antibody biosimilars under review. The biggest targets? Adalimumab (Humira) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda). There are 14 candidates for Humira and six for Keytruda. If even half of those get approved, we’ll see a major shift in how autoimmune diseases and cancers are treated.

The EMA is also preparing new guidelines for even more complex biosimilars-like bispecific antibodies (which target two proteins at once) and antibody-drug conjugates (which carry chemo directly to cancer cells). These are the next frontier. They’re harder to replicate, but if we can make biosimilars of these, the savings could be enormous.

By 2027, IQVIA predicts monoclonal antibody biosimilars will make up 35% of all biologic prescriptions in the U.S., up from 18% in 2022. Cancer therapies will account for 62% of that volume. That means more patients getting effective treatment, at a fraction of the cost.

What This Means for Patients

If you’re on a biologic like Herceptin, Rituxan, or Avastin, your doctor may soon offer a biosimilar option. Ask if it’s right for you. Ask if it’s interchangeable. Ask about cost. You might be surprised how much you can save. And you won’t be giving up anything-because the science says you don’t have to.

Are monoclonal antibody biosimilars as safe as the original drugs?

Yes. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require extensive testing to prove biosimilars have no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, or effectiveness. Large studies involving thousands of patients show similar rates of side effects and immune reactions compared to the original biologics. Rare cases of allergic reactions have occurred, but they are no more common than with the reference product.

Can pharmacists substitute a biosimilar for the brand-name drug without asking my doctor?

Only if the biosimilar is designated as "interchangeable" by the FDA. As of 2023, Remsima (infliximab) is the first monoclonal antibody biosimilar to receive this status. For non-interchangeable biosimilars, a doctor must specifically prescribe the biosimilar. Pharmacists cannot substitute them automatically, unlike with traditional generics.

How much money can I save with a biosimilar?

Savings vary, but most monoclonal antibody biosimilars cost 15% to 35% less than the original drug. In some cases, like switching from rituximab to Truxima, studies have shown a 28% reduction in cost per treatment cycle. For expensive drugs like Keytruda or Herceptin, that could mean thousands of dollars saved per year.

Why are biosimilars cheaper if they’re so complex to make?

Biosimilars don’t need to repeat the full clinical trials that the original drug went through. Instead, manufacturers only need to prove similarity through analytical studies and targeted clinical trials. This cuts development time and cost significantly. They also benefit from existing manufacturing knowledge and infrastructure, which lowers production expenses.

Do biosimilars work for all the same conditions as the original drug?

Yes. Biosimilars are approved for all the same uses (indications) as the reference product, based on a “totality of evidence” approach. This means regulators look at analytical data, animal studies, and clinical trials to confirm similarity across all conditions the original drug treats. For example, a trastuzumab biosimilar can be used for both HER2-positive breast cancer and gastric cancer, just like Herceptin.

Tola Adedipe

February 7, 2026 AT 23:32

This is the kind of shit that actually matters. I work in oncology logistics and seeing biosimilars cut costs by 30%? Game changer. Patients aren't choosing between rent and chemo anymore. We're talking real human impact here. No fluff, just science that works.

Niel Amstrong Stein

February 9, 2026 AT 17:26

Honestly? I used to think biosimilars were just pharma's way of cutting corners. Then my cousin got on a trastuzumab biosimilar for breast cancer. Same results. Half the price. Now I'm just mad we didn't do this sooner 😅 The system was built to protect profits, not people. But hey, science won. 🙌

Joey Gianvincenzi

February 10, 2026 AT 14:57

The regulatory rigor applied to monoclonal antibody biosimilars is unparalleled in pharmaceutical history. The analytical, non-clinical, and clinical evidence packages submitted to the FDA and EMA exceed those of traditional small-molecule generics by orders of magnitude. This is not a compromise; it is a triumph of translational science.

Sarah B

February 12, 2026 AT 11:08

Biosimilars save lives and money period

Eric Knobelspiesse

February 12, 2026 AT 13:55

so like... biosimilars are basically the keto diet of pharma? you know the original drug is the real deal but the copy is kinda close and cheaper and people swear by it?? i mean i get the science but why does it feel like we're still scared to trust it?? like i trust my local pharmacy to swap out my ibuprofen but this?? 🤔

Marcus Jackson

February 13, 2026 AT 14:38

The 28% cost reduction from rituximab to Truxima isn't just a number. It's 1247 patients who didn't have to choose between treatment and their mortgage. The data is solid. The fear? Mostly misinformation. I've reviewed the clinical trial datasets. The PK/PD profiles are nearly identical. The immune response curves? Overlap completely. Stop treating biosimilars like they're risky. They're just better.

Natasha Bhala

February 14, 2026 AT 09:21

i just want to say thank you to whoever wrote this. my mom switched to a biosimilar last year and it saved us so much. she's doing great. no side effects. no drama. just a lighter bill and more peace of mind. you made something complicated feel human. 💛

Jesse Lord

February 16, 2026 AT 08:42

I’ve seen the fear firsthand. Oncologists who won’t prescribe biosimilars because they’re 'not sure.' But here’s the thing - if you’re not sure, look at the data. Look at the real-world studies. Look at the patients who are alive because they got treated. We don’t need perfection. We need access. And biosimilars? They’re delivering.

Catherine Wybourne

February 17, 2026 AT 19:21

So we’ve got a $250 billion savings coming? Cool. But let’s be real - the real win isn’t the money. It’s that a single mom in rural Alabama can now get her daughter’s cancer meds without selling her car. That’s the story nobody talks about. The science is cool. The humanity? That’s the revolution.

Paula Sa

February 18, 2026 AT 10:22

It’s fascinating how the fear around biosimilars mirrors the early resistance to generic antibiotics in the 90s. People were terrified of 'cheap' penicillin. Then we realized: the molecule worked. The outcome mattered. The cost? Just a bonus. We’re at the same inflection point now. The science is clear. The only thing left to overcome is perception.