Every year, millions of people in the U.S. take prescription and over-the-counter medications without issue. But for some, a drug that’s supposed to help ends up causing harm. Maybe you felt dizzy after starting a new blood pressure pill. Or your teenager broke out in a rash after taking an antibiotic. Maybe a loved one ended up in the hospital after a routine shot. These aren’t rare. They’re adverse drug reactions - and they need to be reported.

The FDA doesn’t just approve drugs and walk away. Once a medication hits the market, it’s watched closely. That’s where you come in. Whether you’re a patient, a caregiver, or a healthcare provider, reporting a suspected bad reaction isn’t just helpful - it can save lives. The system that handles this is called MedWatch, and it’s the FDA’s main tool for catching drug safety problems that clinical trials missed.

What Counts as a Reportable Reaction?

Not every side effect needs a report. The FDA defines a serious adverse event as one that:

- Causes death

- Is life-threatening

- Leads to hospitalization or extends an existing hospital stay

- Results in permanent disability or birth defects

- Requires medical intervention to prevent lasting harm

For example: if a new diabetes drug causes severe low blood sugar that lands someone in the ER, that’s reportable. If you get a mild headache after taking ibuprofen, that’s usually not. But if the headache turns into a stroke? That’s serious - and needs reporting.

The FDA gets about 2 million reports a year. But experts say only 6% to 10% of actual serious reactions are reported. That means for every 10 bad reactions, nine go unnoticed. Your report could be the one that triggers a warning, a label change, or even a drug recall.

Who Can Report?

Anyone can report. Patients, family members, nurses, pharmacists, doctors - you don’t need special training or credentials. The FDA encourages reports from all corners, especially from people who see the effects firsthand.

Manufacturers have to report serious reactions within 15 days. Healthcare providers at hospitals or clinics must report if they believe there’s a reasonable chance the drug caused the problem. But if you’re a regular person who noticed something odd after taking a pill? You’re just as important.

Here’s the truth: most reports come from patients and caregivers. A 2022 FDA survey found that nearly 40% of all safety reports came from non-professionals. That’s you.

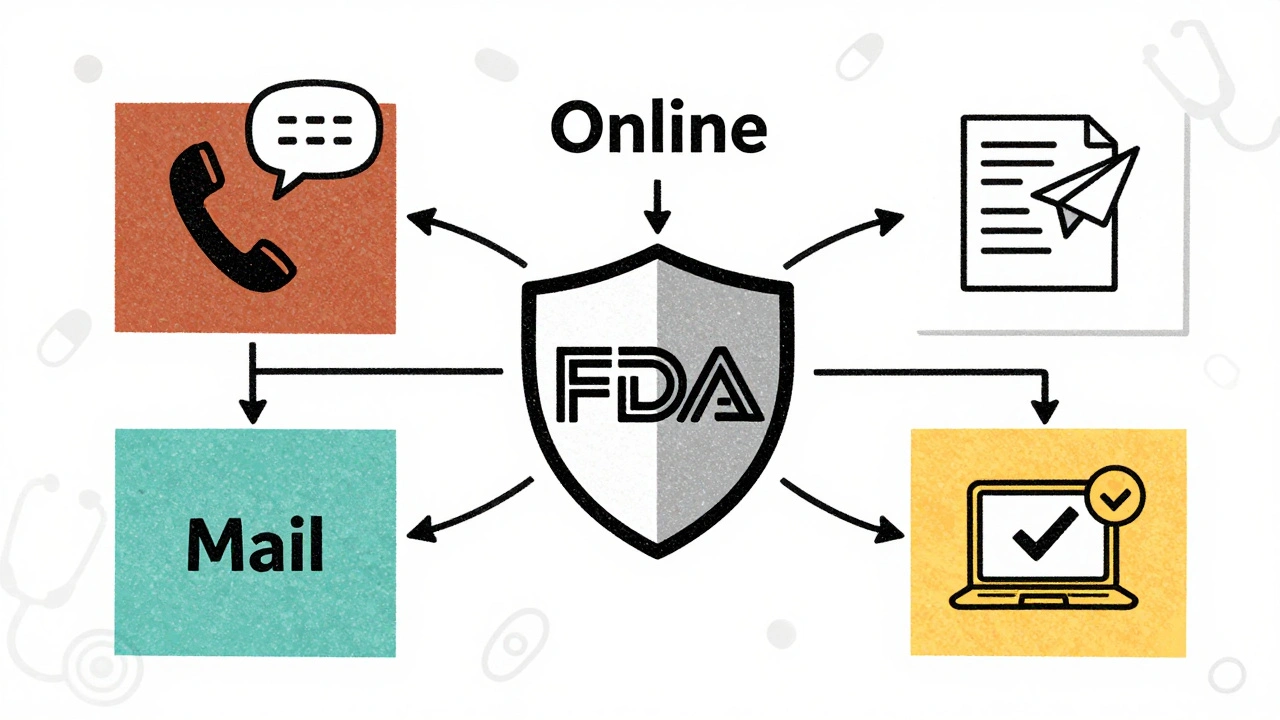

How to Report: Three Simple Ways

You have three easy ways to report. All are free, all are confidential, and all go straight into the FDA’s system.

1. Online - Fastest and Most Common

Go to MedWatch Online and fill out Form 3500. This is the most popular method. You’ll need:

- Patient info (age, sex, weight - if known)

- Drug name (brand or generic)

- Dose and how long they took it

- Date the reaction started

- What happened (be specific: "severe vomiting for 48 hours," not just "felt sick")

- Outcome (recovered, hospitalized, died)

- Your contact info (so they can follow up if needed)

It takes 20 to 25 minutes to complete. The system guides you step by step. You can save and return later if you need to check medical records.

2. Phone - For Urgent Cases

If you’re in a hurry or need help filling out the form, call 1-800-FDA-1088. The line is staffed Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. Eastern time. A trained representative will ask you the same questions as the online form and file it for you. This is especially helpful if you’re dealing with a recent hospitalization or death.

3. Mail - If You Prefer Paper

You can download Form 3500 from the FDA website, print it, fill it out, and mail it to:

FDA MedWatch

5600 Fishers Lane

Rockville, MD 20852-9787

It takes longer, but it’s still valid. If you’re reporting a death or life-threatening event, don’t wait for mail. Use the phone or online option.

What Happens After You Report?

Once the FDA gets your report, it goes into FAERS - the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. This is a massive database with over 20 years of data. Analysts look for patterns. If 10 people report the same rare reaction to the same drug, that’s a signal. If 100 do? That’s a red flag.

One real case: a nurse reported severe low blood sugar in patients taking a new diabetes drug. The FDA reviewed dozens of similar reports. Within 47 days, they updated the drug’s label to warn doctors and patients. That change likely prevented dozens of emergency visits.

Reports aren’t treated as proof that the drug caused the reaction - just as a possible link. But when enough reports pile up, the FDA investigates. They might require new warnings, restrict use, or even pull the drug off the market.

You won’t get a personal reply unless they need more info. That’s normal. The system is designed to find trends, not respond to individuals.

Common Mistakes People Make

Many reports get tossed out because they’re incomplete. Here’s what to avoid:

- Just saying "side effect" - Be specific. "Nausea" isn’t enough. Say "vomiting 6 times a day for 3 days after taking the pill."

- Not including the drug name - If you don’t know the generic name, write the brand name and the pill’s color and shape. The FDA can look it up.

- Waiting too long - If it’s serious, report it as soon as you can. Even if it happened months ago, report it. It still counts.

- Thinking it’s not serious enough - If you’re unsure, report it anyway. The FDA’s experts will decide if it matters.

Also, don’t wait for your doctor to report it. Many don’t have time. A 2022 AMA survey found 63% of providers said lack of time was their biggest barrier. Your report might be the only one they ever file.

Why Your Report Matters

Drug safety isn’t just about science. It’s about people. Clinical trials test drugs on a few thousand people. Real life? Millions. Different ages, other meds, chronic conditions - things trials can’t catch.

Take the case of Vioxx. It was pulled in 2004 after thousands of heart attacks and strokes were reported. The warning signs were there - but they were buried in scattered reports. If more people had reported earlier, the drug might have been pulled sooner.

Today, the FDA uses AI to scan reports for patterns. But AI can’t see what you see. Only a human can say, "My mother took this and stopped walking." That kind of detail changes everything.

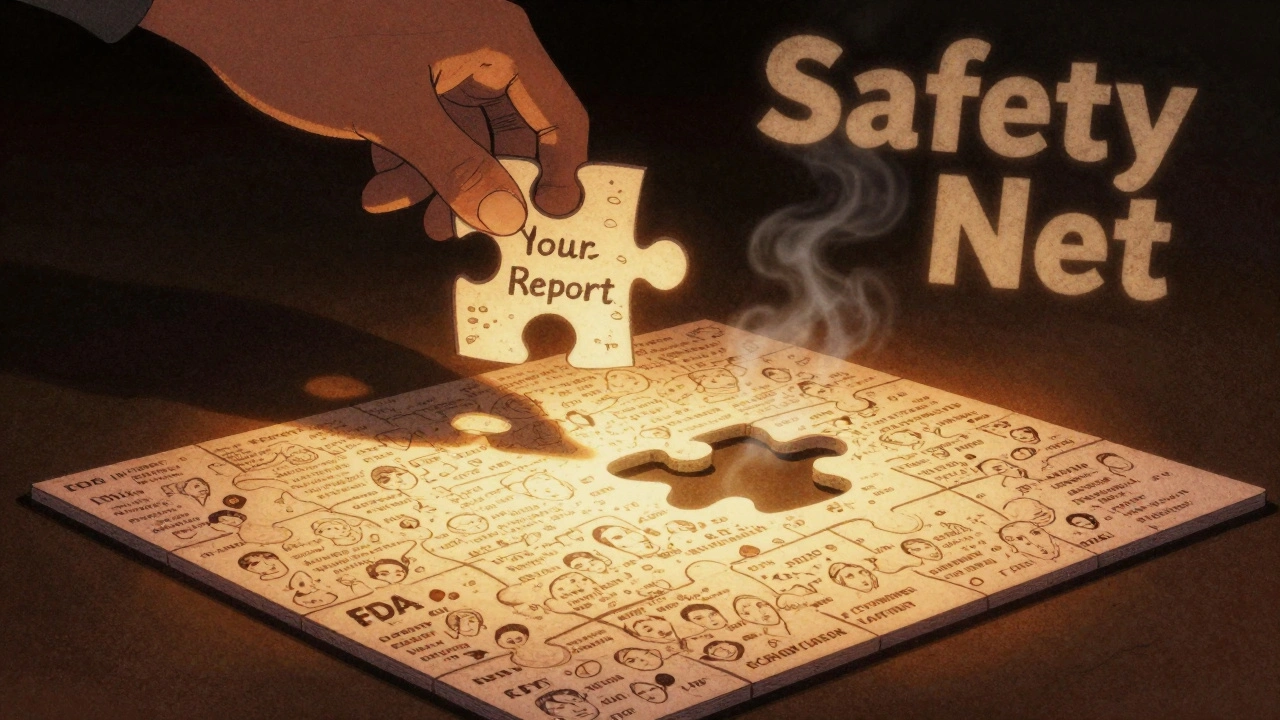

Reporting isn’t about blaming. It’s about protecting. Every report adds a piece to the puzzle. And sometimes, that one piece is the one that stops the next tragedy.

What’s Changing Soon?

The FDA is making reporting easier. By the end of 2025, electronic health record systems will automatically send safety alerts to the FDA. That’s good - but it doesn’t replace your role.

Patients still need to report reactions that aren’t in medical records - like reactions to over-the-counter drugs, supplements, or drugs taken at home. And social media reports? Starting in 2025, manufacturers will have to monitor platforms like Reddit and Twitter for mentions of bad reactions and report them.

But you? You’re still the frontline. No algorithm can replace your voice.

Need Help? Here’s Where to Call

If you’re stuck filling out the form, have questions about what to report, or need help understanding a drug’s side effects:

- Call MedWatch Safety Information: 1-800-FDA-1088 (8 a.m. to 10 p.m. ET)

- Email [email protected] for technical issues - they respond within 24 hours

- Watch free 90-minute FDA webinars on adverse event reporting (held monthly)

There’s no penalty for reporting. No one will track you down. Your name stays confidential unless you choose to share it. And you won’t be asked to pay anything.

Reporting a reaction isn’t a burden. It’s a responsibility - and a powerful one. The next person who takes that same drug might walk away healthy because you spoke up.

Do I need to prove the drug caused the reaction to report it?

No. You don’t need to prove causation. The FDA’s job is to collect possible links - not confirm them. If you suspect a drug caused a reaction, report it. Experts will analyze the data later to see if there’s a pattern. Many reports are dismissed as unrelated - but others lead to life-saving changes.

Can I report a reaction to a supplement or herbal product?

Yes. The FDA accepts reports for dietary supplements, vitamins, and herbal products. These aren’t regulated like prescription drugs, so reports are even more important. If you had a bad reaction to a weight-loss tea, energy pill, or CBD product, report it. The FDA tracks these closely.

Will my doctor find out I reported the reaction?

No. Your report is confidential. The FDA does not share your name or contact details with your doctor, pharmacy, or drug manufacturer unless you give permission. Your privacy is protected by federal law.

What if I report a reaction and nothing happens?

That’s normal. Most reports are single events. But if 50 others report the same thing, the FDA takes action. One report might seem small - but it’s part of a bigger picture. Think of it like a smoke detector: you don’t know if it saved a life until the fire comes. Your report helps build that early warning system.

Can I report a reaction for someone else?

Absolutely. Parents, caregivers, and family members can report for loved ones - especially if they’re elderly, disabled, or unable to report themselves. Just list yourself as the reporter and the patient’s details as the subject.

How long does it take for the FDA to act on a report?

There’s no set timeline. Some signals are caught in weeks; others take years. It depends on how many similar reports come in and how serious the reaction is. But every report gets logged and analyzed. Even if you don’t see a change, your report is still part of the safety net.

Bruno Janssen

December 12, 2025 AT 13:48

I reported my mom's reaction to that new statin last year. She got severe muscle pain and couldn't walk for weeks. I filled out the form online after midnight, exhausted, crying. No one ever called back. No email. Just silence. But I did it anyway. Because if not me, who?

Scott Butler

December 13, 2025 AT 20:47

Why are we letting random people report drug reactions? This isn't a Yelp review. The FDA should only listen to licensed professionals. Half these reports are from people who don't even know what a generic name is. We're drowning in noise while real science gets ignored.

Emma Sbarge

December 15, 2025 AT 10:44

Scott, you're missing the point. The whole reason this system exists is because clinical trials are too small. My sister had a rare reaction to a common antibiotic - her doctor didn't even know it was possible. But after three other people reported it, the FDA added a black box warning. That's not noise. That's survival.

Donna Hammond

December 16, 2025 AT 22:50

Let me tell you something that no one else will: reporting isn’t about getting a response. It’s about adding your voice to a database that saves lives - even if you never see the outcome. I’ve been a pharmacist for 22 years. I’ve seen drugs pulled because of a single report from a grandmother who noticed her grandson stopped talking after taking a new ADHD med. That’s not luck. That’s data. And it only works when people like you and me take five minutes to type it out. You think it doesn’t matter? Look at Vioxx. Look at fen-phen. Look at the opioid crisis. The warnings were there - buried under silence. Don’t be silent. Report. Even if it’s just one line. One line can be the thread that pulls the whole tapestry together.

Sheldon Bird

December 17, 2025 AT 10:13

Hey, I just reported my kid's rash after the flu shot. Felt weird, but I didn’t want to panic. Took me 18 minutes online - the form was actually super easy. Didn’t even need my medical records. Just typed what happened. No judgment. No pressure. Just a button that says ‘Submit.’ And now I feel like I did something real. Thanks for the guide - this is how we fix things, one report at a time. 💪

Karen Mccullouch

December 17, 2025 AT 10:58

They’re coming for our meds. You think this is about safety? Nah. This is the first step. They want to control what we take. Next thing you know, they’ll ban supplements, then vitamins, then caffeine. They’re tracking every cough, every headache, every sneeze. And when enough people report ‘side effects,’ they’ll say ‘see? It’s dangerous.’ Then they’ll take it away. Don’t feed the machine.

Willie Onst

December 18, 2025 AT 07:05

Man, I love that this system exists. I used to think only doctors could make a difference. Then my buddy’s dad had a bad reaction to a generic blood pressure med - the doctor didn’t even know it was possible. We filed a report. Three months later, the FDA issued a warning. My buddy cried. Said his dad might’ve died if no one spoke up. That’s the power of ordinary people doing something ordinary. We’re not just patients. We’re guardians. Keep reporting. Keep showing up. The system only works if we do.

Jennifer Taylor

December 19, 2025 AT 08:50

Wait - so the FDA is watching Reddit now? And they’re going to force companies to monitor Twitter? That’s it. I knew it. They’re building a surveillance state under the guise of ‘safety.’ Next they’ll scan your smart fridge for your vitamin intake. They’ll use AI to flag your Fitbit data as ‘possible adverse reaction.’ They’ll call you in for ‘evaluation.’ They already know your name. They know your meds. They know your grocery list. This isn’t protection. It’s control. And they’re using your fear to get it. Don’t play along. Don’t report. Don’t give them data. They don’t want to help you. They want to own you.

Shelby Ume

December 19, 2025 AT 11:15

As someone who works in public health policy, I want to thank the author for this clear, actionable guide. Many patients don’t realize that reporting to MedWatch isn’t just a formality - it’s a critical component of post-market surveillance. The system is designed for low-barrier, high-impact participation. Even incomplete reports contribute to signal detection algorithms. I’ve reviewed FAERS data for over a decade. The most impactful reports often come from caregivers of elderly patients who can’t navigate the system themselves. Please report. Even if you’re unsure. Even if you’re tired. Even if you think it’s ‘not that bad.’ The collective weight of these reports is what turns anecdotes into action. This is how public health works - not in grand pronouncements, but in quiet, persistent acts of care.