Parathyroidectomy Decision Guide

Key Clinical Criteria for Surgery

- Persistent PTH > 800 pg/mL despite optimal medical therapy

- Severe hypercalcemia or hyperphosphatemia causing complications

- Severe symptoms like bone pain, fractures, or pruritus

- Medication intolerance or contraindications

Consider Medical Management If:

- Early CKD (stage 3-4) with mild PTH elevation

- High surgical risk factors

- Strong patient preference against surgery

- Good response to current medications

Parathyroidectomy is a surgical procedure that removes one or more of the parathyroid glands to control excess parathyroid hormone (PTH) production. It is most often considered for patients with Secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) when medical therapy no longer keeps PTH, calcium, and phosphate levels in a safe range.

- SHPT is driven by chronic kidney disease (CKD)-related mineral disturbances.

- Medical options include calcimimetics, vitamin D analogues, and phosphate binders.

- Surgery is indicated when PTH stays >800 pg/mL, calcium‑phosphate product is persistently high, or symptoms worsen.

- Subtotal or total parathyroidectomy with autotransplant offers durable PTH control for most patients.

- Post‑op monitoring and lifelong supplementation are essential.

Understanding Secondary Hyperparathyroidism

Secondary hyperparathyroidism arises when the kidneys can’t excrete phosphate or activate vitamin D, leading to low calcium levels. The parathyroid glands respond by overproducing PTH, which tries to pull calcium from bones, raise intestinal absorption, and mobilize phosphate. Over time, the glands enlarge (hyperplasia) and become less responsive to feedback.

Key attributes of SHPT include:

- CKD stage 3‑5 or on dialysis (average prevalence >70% in dialysis patients).

- PTH levels often exceed 600‑800 pg/mL.

- Associated complications: bone pain, vascular calcifications, pruritus, and increased mortality.

Why Consider Parathyroidectomy?

Medical therapy can control SHPT for many, but about 15‑20% of dialysis patients become refractory. Indications for surgery typically involve:

- Persistently high PTH (>800 pg/mL) despite maximized calcimimetic and vitamin D analogue doses.

- Severe hypercalcemia or hyperphosphatemia causing calciphylaxis or cardiac calcifications.

- Bone pain, fractures, or severe pruritus unresponsive to meds.

- Intolerance to high‑dose medications (e.g., gastrointestinal side‑effects from calcimimetics).

When these criteria are met, parathyroidectomy offers the most reliable way to bring PTH down to target levels (<400 pg/mL) and halt disease progression.

Pre‑operative Assessment

Before heading to the OR, a multidisciplinary team evaluates the patient:

- Laboratory work: PTH, calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase, 25‑OH vitamin D, and 1,25‑(OH)₂ vitamin D.

- Imaging: Neck ultrasound or sestamibi scan to locate hyperplastic glands.

- Cardiovascular screening: Echo or CT to assess vascular calcifications that may affect anesthesia.

- Nutrition assessment: Ensure adequate protein and calcium intake for healing.

Patients with uncontrolled hypertension or severe cardiopulmonary disease may need optimization before surgery.

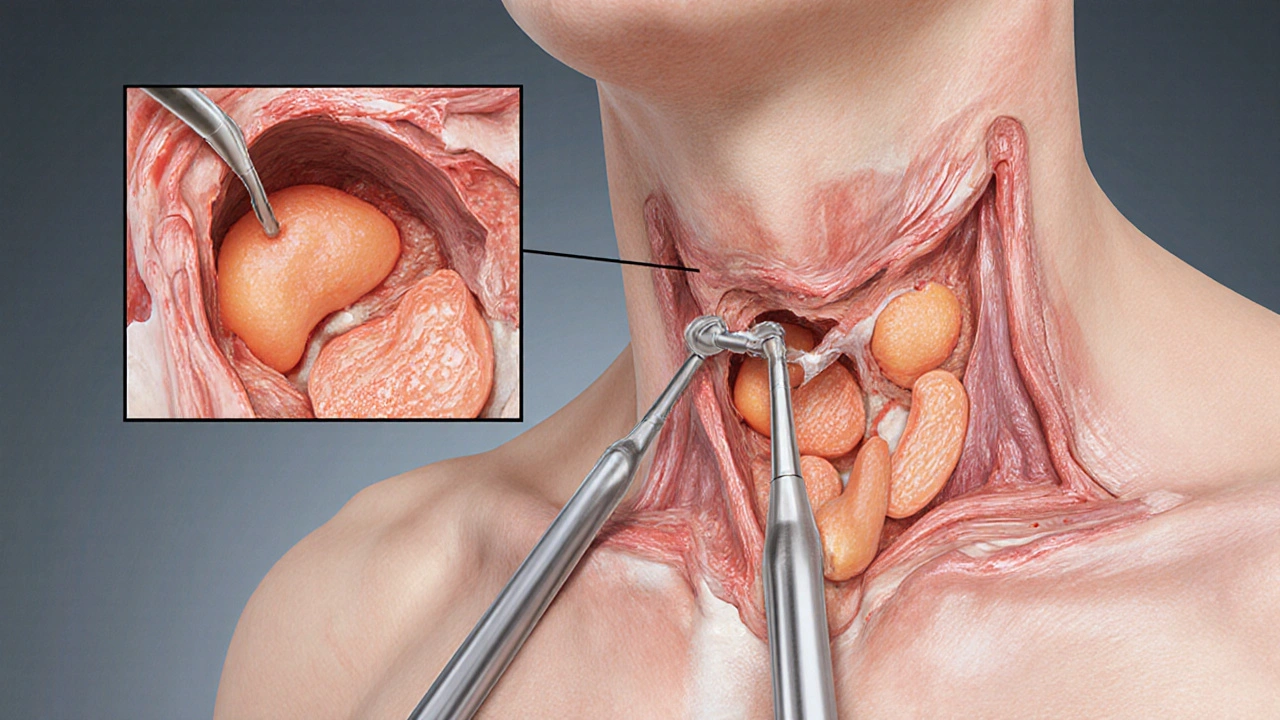

Surgical Techniques

The two main approaches are:

- Subtotal parathyroidectomy - removal of 3½ glands, leaving a small remnant (≈30‑50 mg) in situ.

- Total parathyroidectomy with autotransplant - all four glands are removed, and a slice of healthy tissue is implanted in the forearm muscle.

Both techniques aim to keep enough PTH to avoid hypocalcemia while preventing hypersecretion. The autotransplant method makes any future re‑exploration easier because the graft can be accessed under local anesthesia.

Outcomes and Evidence

Large registry data from the United States Renal Data System (2023) show that patients undergoing parathyroidectomy have:

- Mean PTH reduction of 78% at 6months.

- Improved bone mineral density (average +12% at lumbar spine).

- Reduced all‑cause mortality (hazard ratio0.84) compared with patients staying on medical therapy alone.

Complication rates are low when performed at high‑volume centers:

- Transient hypocalcemia: 15‑20% (managed with calcium infusion).

- Permanent hypoparathyroidism: <2%.

- Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury: 1‑3%.

Long‑term graft failure after autotransplant occurs in about 5% of cases, often requiring repeat surgery.

Medical Alternatives: When Surgery Isn’t First‑Line

Before jumping to the OR, clinicians typically try a stepped medical regimen:

- Calcimimetics (e.g., cinacalcet, etelcalcetide) lower PTH by increasing the sensitivity of the calcium‑sensing receptor.

- Vitamin D analogues (e.g., paricalcitol, doxercalciferol) suppress PTH transcription.

- Phosphate binders (sevelamer, calcium acetate) reduce serum phosphate, indirectly reducing PTH stimulus.

These drugs can be combined, but they have limits: calcimimetics cause nausea and hypocalcemia; high‑dose vitamin D raises calcium and phosphorus; binders add pill burden.

| Aspect | Parathyroidectomy | Medical Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Mean PTH reduction | ≈78% (6mo) | 30‑50% (max dose) |

| Impact on bone density | +12% lumbar spine | Variable, modest |

| Risk of severe hypocalcemia | Transient 15‑20% | Low, but possible with calcimimetics |

| Long‑term survival benefit | HR0.84 (USRDS 2023) | Neutral to slight benefit |

| Cost (first‑year) | Procedural fee + hospital stay ≈ $15,000 | Annual meds ≈ $10,000‑$12,000 |

Risks, Complications, and Post‑operative Care

Even with a skilled surgeon, patients should be aware of possible issues:

- Hypocalcemia: Most common in the first 48hours. Monitor ionized calcium every 4‑6hours; give IV calcium gluconate if below 0.9mmol/L.

- Neck hematoma: Rare but can compress airway; observe for 24hours.

- Recurrent hyperparathyroidism: Happens in 5‑10% due to missed supernumerary glands.

- Permanent hypoparathyroidism: Lifelong calcium and active vitamin D supplementation.

After discharge, patients need:

- Weekly calcium & PTH labs for the first month.

- Gradual taper of calcitriol; many stay on low‑dose vitamin D analogues.

- Dietary counseling to maintain calcium 1,000‑1,200mg/day and limit phosphate.

- Bone density scan at 12months to assess response.

Decision Guide: Who Benefits Most?

Put the options on a simple matrix:

- Better for surgery: Patients on dialysis >5years, PTH >800pg/mL, refractory bone pain, or calciphylaxis.

- Better for meds: Early CKD (stage3‑4), mild PTH elevation, high surgical risk, or strong preference to avoid operation.

In practice, many centers adopt a “step‑up” strategy: start with maximal medical therapy, then refer for parathyroidectomy if targets aren’t met within 6‑12months.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the recovery time after parathyroidectomy?

Most patients leave the hospital in 2‑3days. Full recovery, including wound healing and stable calcium levels, usually takes 4‑6weeks. Light activity is fine after the first week, but heavy lifting should be avoided until the incision is fully healed.

Can parathyroidectomy be performed on peritoneal dialysis patients?

Yes. The surgery itself is independent of the dialysis modality. However, peritoneal dialysis patients need careful fluid management and may require temporary hemodialysis around the operation.

What happens if the disease recurs after surgery?

Recurrence is usually due to missed or supernumerary glands. A repeat imaging work‑up can locate the culprit, and a second‑look surgery (often through the forearm graft) can restore control.

Is there an age limit for parathyroidectomy?

Chronological age alone isn’t a barrier. Functional status, cardiovascular health, and anesthesia risk drive the decision. Many patients over 75years undergo the procedure safely when benefits outweigh risks.

Do I need to stop calcimimetics before surgery?

Typically, calcimimetics are held the night before the operation to avoid intra‑operative hypocalcemia. They can be restarted once calcium levels stabilize post‑op.

Alex Feseto

October 3, 2025 AT 12:43

In the elaborate discourse surrounding secondary hyperparathyroidism, the surgical threshold is often delineated by a constellation of biochemical imperatives. Persistent PTH concentrations exceeding eight hundred picograms per millilitre, despite maximal pharmacologic optimisation, constitute a compelling indication for parathyroidectomy. Equally, refractory hypercalcaemia or hyperphosphataemia that precipitates vascular calcification demands decisive operative intervention. The operative strategy customarily favours subtotal gland excision with autotransplantation, thereby preserving residual physiological regulation. Post‑operative vigilance, encompassing calcium supplementation and serial PTH monitoring, remains indispensable to avert hypocalcaemic sequelae.

vedant menghare

October 8, 2025 AT 07:06

My dear colleagues, let us consider the broader tapestry that frames the decision to excise parathyroid tissue in those beleaguered by chronic kidney dysfunction.

When the renal excretory capacity wanes, phosphate accumulates, and the skeletal reservoir releases calcium in a desperate attempt to sustain homeostasis, the parathyroids swell in a bid to compensate.

In many of my patients back home, the relentless surge of PTH above eight hundred, even after titrating calcimimetics to the brink, heralds an inexorable march toward bone demineralisation and pruritic torment.

One cannot overstate the psychological burden of incessant itching and skeletal fragility; it erodes quality of life more insidiously than any laboratory number.

Thus, the surgeon’s scalpel becomes not merely a tool but a compassionate instrument of relief.

Nevertheless, prudence dictates that we first exhaust the pharmacologic arsenal-high‑dose vitamin D analogues, sevelamer, and the newest calcimimetics-while meticulously monitoring calcium‑phosphate product to keep it below the ominous seventy milligram‑squared per decilitre threshold.

Should these measures falter, the pendulum swings decisively toward operative management.

It is heartening to note that contemporary centres report postoperative PTH reductions to near‑physiologic ranges in upwards of ninety percent of cases, with attendant improvements in bone pain scores and pruritus intensity.

Equally important is the multidisciplinary choreography involving nephrologists, surgeons, and dietitians to ensure seamless transition around the peri‑operative window.

Patients on peritoneal dialysis, for instance, often require a temporary shift to haemodialysis to mitigate fluid imbalances during the surgical admission.

Furthermore, the specter of hypocalcaemia looms post‑resection, mandating vigilant calcium replacement and perhaps a brief stint of intravenous calcium gluconate.

In my experience, the majority of individuals regain functional independence within six weeks, and the lingering fear of recurring hyperparathyroidism subsides with regular follow‑up imaging and lab surveillance.

In sum, while the decision matrix is intricate, the judicious use of parathyroidectomy-reserved for those who have truly exhausted medical options-offers a beacon of hope amidst the relentless tide of CKD‑related mineral bone disorder.

May we continue to tailor our interventions with both scientific rigour and compassionate empathy.

Kevin Cahuana

October 12, 2025 AT 22:13

Thanks for laying out such a vivid picture, especially the part about the multidisciplinary dance-it's easy to forget how much coordination it takes. I’ve seen patients bounce back nicely once the calcium levels are stabilised, and the itching finally eases up. It really underscores why we need to keep pushing through the medical steps before jumping to the OR.

Natalie Kelly

October 17, 2025 AT 13:20

Totally get the surgery anxiety, but if you’re hitting those PTH numbers your docs will push you. Keep the meds up till then.

Tiffany Clarke

October 22, 2025 AT 04:26

Honestly surgery feels like last resort but sometimes necessary.

Sandy Gold

October 26, 2025 AT 18:33

Well, everyone loves to shout about "guidelines" while ignoring the fact that a lot of these recommendations are based on shaky evidence from small cohorts. In my opinion, we should be more skeptical before defaulting to an invasive procedure that carries its own morbidities.

Frank Pennetti

October 31, 2025 AT 09:40

From a systems‑level perspective, the cost‑benefit analysis of parathyroidectomy versus lifelong pharmacotherapy is non‑trivial; the high‑density jargon of health economics often masks the pragmatic reality that surgery, when indicated, can curtail downstream vascular calcification, thereby reducing long‑term cardiovascular expenditures.

Adam Baxter

November 5, 2025 AT 00:46

Surgery works, period.

Keri Henderson

November 9, 2025 AT 15:53

That’s the bottom line-if meds fail, the scalpel gets the job done fast and saves you from endless pill burdens.

elvin casimir

November 14, 2025 AT 07:00

While I appreciate the enthusiasm, let us not overlook the imperative of meticulous pre‑operative evaluation; a comprehensive cardiac assessment and anesthesia risk stratification are non‑negotiable prerequisites before proceeding to parathyroidectomy.

Katey Nelson

November 18, 2025 AT 22:06

Indeed, the pre‑operative checklist is akin to a philosophical ritual, reminding us that every incision is a pact between flesh and fate 😊.

We must interrogate not only the biochemical thresholds but also the patient’s psychosocial readiness, for a mind unsettled by surgery may sabotage even the most technically flawless operation.

In addition, the postoperative care plan should integrate dietary counseling, precise calcium titration, and vigilant surveillance for hungry bone syndrome, which, if ignored, can precipitate a cascade of complications that echo far beyond the operating theatre.

Thus, the decision to operate transcends mere numbers; it is a holistic covenant with the patient’s future health.

Joery van Druten

November 23, 2025 AT 13:13

Just a quick tip: when documenting postoperative calcium levels, use the format "Ca (mg/dL): X.Y" to keep everything consistent and avoid confusion during multidisciplinary rounds.

Melissa Luisman

November 28, 2025 AT 04:20

That’s an okay suggestion, but you really should write "Calcium (mg/dL):" – the word "Calcium" must be capitalized and the unit placed in parentheses for proper notation.

Alice Witland

December 2, 2025 AT 19:26

Oh sure, because we’ve all got unlimited access to top‑tier surgeons and can just breeze through a parathyroidectomy without a second thought. Realistic, isn’t it?

Chris Wiseman

December 7, 2025 AT 10:33

One could argue that the very notion of "unlimited access" is a comforting illusion perpetuated by an inequitable healthcare system.

While the clinical criteria for surgery are crystal clear-PTH > 800, refractory hypercalcaemia, debilitating bone pain-the sociopolitical scaffolding that determines who gets to the operating room first is riddled with bias.

Thus, the decision tree is not just a medical algorithm but also a commentary on resource allocation, patient advocacy, and systemic inertia.

In the end, the surgeon’s scalpel may be sharp, but the knife of bureaucracy can be far more cutting.

alan garcia petra

December 12, 2025 AT 01:40

Let’s keep the momentum going! If you’re on dialysis and your labs are screaming, talk to your team today-there’s no time like the present to explore all options.

Allan Jovero

January 5, 2026 AT 11:43

Allow me to correct a minor inaccuracy: the calcium‑phosphate product threshold is typically cited as 55 mg²/dL², not 70 mg²/dL² as previously mentioned.