When a brand-name drug’s patent is about to expire, the race to bring out a cheaper generic version begins - not with a product launch, but with a legal notice. That notice is called a Paragraph IV certification, and it’s the key that unlocks the door to generic competition in the U.S. pharmaceutical market. Without it, most generics would wait years after patent expiry, leaving patients paying high prices. But Paragraph IV doesn’t just speed things up - it triggers a high-stakes legal battle that can take years, cost millions, and change how much you pay for your meds.

What Exactly Is Paragraph IV?

Paragraph IV isn’t a law. It’s a section of the Hatch-Waxman Act, passed in 1984. This law was designed to balance two goals: protecting innovation by giving drugmakers time to recoup R&D costs, and making medicines affordable by letting generics enter the market faster. The Paragraph IV certification is how a generic drug company says to the brand-name maker and the FDA: "Your patent is invalid, unenforceable, or we’re not breaking it. Let us sell our version." This isn’t a casual claim. It’s a formal legal statement filed with the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). The generic company must prove it - not just say it. They need to lay out the scientific and legal reasons why the patent doesn’t hold up. That could mean showing prior art that existed before the patent was filed, or proving the invention was obvious to someone skilled in the field. Or, they might show that their version doesn’t actually use the patented method or formula.How the Process Unfolds

Here’s how it works step by step:- A generic manufacturer picks a brand-name drug listed in the FDA’s Orange Book - the official directory of approved drugs and their patents.

- They analyze every patent listed for that drug. Most drugs have multiple patents: one for the active ingredient, others for how it’s made, how it’s taken, or even the color of the pill.

- If they find a patent they think they can challenge, they file an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification.

- Within 20 days, they must send a detailed notice to the brand-name company, explaining exactly why they believe the patent is invalid or not infringed.

- The brand company has 45 days to sue for patent infringement. If they do, an automatic 30-month clock starts - the FDA can’t approve the generic until that clock runs out, unless the court rules in the generic’s favor earlier.

- During those 30 months, both sides fight in federal court. The battle usually centers on claim construction - what the patent actually covers. A judge holds a Markman hearing to define the key terms in the patent claims. That single hearing often decides the whole case.

- If the generic wins, the FDA approves the drug immediately. If the brand wins, the generic waits until the patent expires.

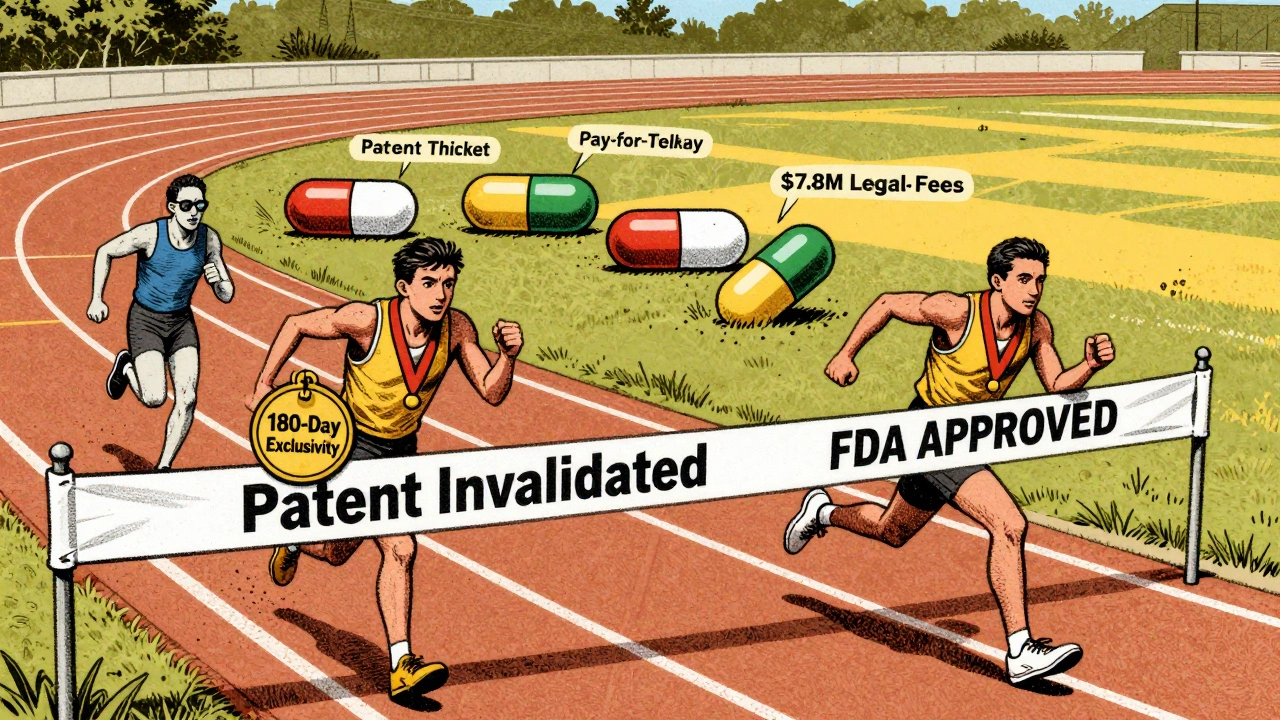

Here’s the kicker: the first company to file a successful Paragraph IV gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell the generic version. No one else can enter the market during that time. That’s why companies fight so hard to be first. In 2014, the FTC found that 87% of Paragraph IV filers were trying to be the first-to-file.

Why This System Works - and Why It’s Broken

The system works because it’s a gamble. The brand company risks losing its monopoly. The generic company risks losing millions if they lose the case. But the reward is huge. When Barr Labs challenged Eli Lilly’s Prozac patent in 1996, they won. Their 180-day exclusivity period let them capture nearly all of the generic fluoxetine market - and they made billions. But the system has been gamed. Brand companies now file multiple patents - an average of 4.8 per drug in 2020, up from just 1.2 in 1984. These are often secondary patents: on pill coatings, dosing schedules, or delivery methods. They’re not the core invention, but they’re enough to block generics. This is called patent thicketing. AbbVie’s Humira, for example, had over 100 patents listed. Generic companies spent years and tens of millions trying to chip away at them - and most failed. Another problem: pay-for-delay. Before 2013, brand companies would sometimes pay generic firms to delay entry. The FTC called it "bribery." The Supreme Court shut it down in FTC v. Actavis, but subtle versions still exist. Some settlements include deals where the brand pays the generic to stay out of the market for a certain time - just not in plain cash.

Success Rates and Costs

Paragraph IV challenges succeed about 65% of the time, according to a UNC study of over 1,700 cases. That’s a lot higher than post-grant reviews at the USPTO, which only succeed 35% of the time against pharma patents. But Paragraph IV is far more expensive. The average cost? $7.8 million per case. Compare that to an Inter Partes Review at the USPTO, which runs around $2.1 million. The cost isn’t just legal fees. Generic companies spend an average of $2.3 million just on pre-filing analysis - studying the patent, running lab tests, preparing claim construction arguments. If they get the notice wrong, the FDA rejects it. In 2018-2022, 63% of rejected Paragraph IV notices failed because the legal basis was too weak. And if they lose? The penalties can be brutal. Mylan was ordered to pay $1.1 billion to Novartis in 2017 for willfully infringing the Gleevec patent. That’s not a fine - it’s a company-ending hit.What Happens After Approval?

When the generic finally enters, prices drop fast. Professor Margaret Kyle’s 2019 study found that prices fell by 79% on average within six months of generic entry. In 2021 alone, Paragraph IV challenges opened the door for 287 brand-name drugs to go generic - saving consumers $98.3 billion in potential spending. The FTC estimates that between 2009 and 2019, generic drugs entering via Paragraph IV saved U.S. consumers $1.68 trillion. That’s not just a number - it’s insulin, heart meds, antidepressants, and cancer drugs suddenly becoming affordable. But here’s the catch: that 180-day exclusivity window means the first generic company charges a premium. They’re the only one allowed to sell. So while the price drops 79%, it doesn’t drop to the rock-bottom level you’d see after 10 competitors enter. That only happens after the exclusivity period ends.

How the Rules Are Changing

The system is under pressure. The FDA now requires Paragraph IV filers to challenge all Orange Book patents, not just the main ones. That makes filings more complex and expensive. The 2023 CREATES Act helps generics get the samples they need to test bioequivalence - something brand companies used to withhold to delay approval. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 lets Medicare negotiate drug prices. That changes the game. If the government can force a brand to lower its price, the incentive to delay generics weakens. Brand companies might be less willing to fight long legal battles if they know Medicare will cap their profits anyway. And now, the FTC is pushing for reform. They’re targeting patent thickets and evergreening. The Congressional Budget Office found that effective market exclusivity - the time a drug stays without generic competition - has grown from 12.1 years in 1995 to 14.7 years in 2022. That’s not because of innovation. It’s because of legal strategy.What This Means for Patients

You don’t need to understand patent law to feel its impact. When a drug you take goes generic, your co-pay drops from $150 to $10. Your insurance stops denying coverage. You stop choosing between buying meds and paying rent. Paragraph IV is the engine that makes that happen. It’s not perfect. It’s expensive, slow, and often manipulated. But it’s the only mechanism in the U.S. that forces patent holders to prove their claims in court before blocking cheaper alternatives. In Europe, there’s no equivalent. Generic drugs take longer to arrive. In the U.S., patients get faster access - but only because someone is willing to spend millions to challenge a patent. The system works because it’s risky. And it works because the reward - lower prices - is worth it.What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement filed by a generic drug company with its ANDA application, claiming that a patent listed for the brand-name drug is invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed by the generic version. This triggers a 30-month regulatory stay and potential patent litigation.

Why does the 30-month stay matter?

The 30-month stay blocks the FDA from approving the generic drug while patent litigation plays out. It gives brand companies time to defend their patents, but it also creates pressure for settlements. If the court rules for the generic before 30 months, approval happens immediately.

Who gets the 180-day exclusivity?

The first generic company to file a substantially complete ANDA with a successful Paragraph IV certification gets 180 days of market exclusivity. During that time, no other generic can enter - even if they’ve also challenged the patent.

How often do Paragraph IV challenges succeed?

About 65% of Paragraph IV challenges succeed in court, according to studies of cases from 1985 to 2010. Success usually depends on whether the patent is weak - for example, based on obviousness or prior art - and how well the generic company constructs its legal argument.

Can brand companies delay generic entry without litigation?

Yes. Brand companies often file multiple secondary patents (on coatings, dosing, or delivery methods) to create "patent thickets." They also use FDA citizen petitions to delay approval, or withhold drug samples needed for bioequivalence testing. The CREATES Act and new FDA rules are trying to stop these tactics.

Ben Greening

December 10, 2025 AT 15:22

The Paragraph IV system is a fascinating example of how legal frameworks can inadvertently create market distortions. It's not just about patents-it's about incentive structures. The 180-day exclusivity window, while meant to encourage challenges, ends up creating a monopoly within a monopoly. The first filer becomes the gatekeeper, not the liberator. And the cost? Millions spent on lawyers instead of R&D. It’s efficient in theory, but morally murky in practice.

Nikki Smellie

December 11, 2025 AT 22:39

Let me be perfectly clear: this entire system is a coordinated deception orchestrated by Big Pharma and the FDA to maintain artificial scarcity. The "patent thickets" aren't accidents-they're deliberate traps. Every secondary patent is a landmine planted to scare off generics. And the 30-month stay? A legal shield for corporate greed. The FTC knows this. Congress knows this. But they're all paid off. Look at the campaign donations. Look at the revolving door. This isn't law-it's extortion dressed in legalese.

David Palmer

December 12, 2025 AT 23:44

So basically, some company spends millions to say "this patent is dumb," and if they win, they get to be the only one selling the cheap version for half a year? That’s wild. Like, why not just let everyone in at once? Who decided this was fair? Also, why do pills have patents on their color? That’s not science, that’s branding. I just want my meds to not cost a month’s rent.

Doris Lee

December 14, 2025 AT 21:18

This is such an important topic and you broke it down so clearly. I’ve had to choose between my insulin and groceries more times than I can count. Knowing there’s a system-even a flawed one-that can make a difference gives me hope. Keep shining light on these issues. Real people are counting on it.

Jack Appleby

December 14, 2025 AT 22:22

It's fascinating how the legal architecture of Paragraph IV reveals the epistemological instability of patent law itself. The Markman hearing-where judicial interpretation of claim construction becomes the arbiter of pharmaceutical access-is a jurisprudential absurdity. The patent system, as currently constituted, conflates technical novelty with economic rent-seeking. The 65% success rate isn't a measure of validity-it's a measure of litigation asymmetry. The generics win not because the patents are weak, but because the brand firms overreach. And let's not ignore the perverse incentive: the first filer is rewarded with monopolistic pricing. This isn't competition. It's legalized oligopoly.

Rebecca Dong

December 16, 2025 AT 02:17

They’re lying. EVERYONE is lying. The FDA doesn’t want generics. The courts are bought. The 180-day window? A trap. The first filer is always a shell company owned by the brand. That’s why Humira still has no real competition after 15 years. They let one fake generic in, collect the exclusivity profits, then bury the rest. And the CREATES Act? A PR stunt. The samples? Still withheld. I’ve seen the emails. The lawyers are laughing. You think this is about health? It’s about stock prices. And you? You’re the mark.

Regan Mears

December 17, 2025 AT 20:44

Thank you for writing this. I’ve been reading about this for months, and it’s hard to find clear explanations. I’m a nurse, and I see patients skip doses because they can’t afford the brand. I’ve had to cry with them. The fact that a single legal filing can change someone’s life-by cutting a $300 pill to $15-isn’t just policy. It’s human. Yes, the system is broken. But it’s the only tool we have right now. Let’s fix the loopholes, not abandon the mechanism. The 180-day window needs reform, but the core idea? It saves lives. Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Neelam Kumari

December 19, 2025 AT 19:41

Wow. You actually believe this system works? In India, we don’t have Paragraph IV. We just make the generic and sell it. No lawsuits. No 30-month delays. No million-dollar legal teams. The patent? We ignore it. And guess what? People live. You call this innovation? We call it survival. Your system isn’t about access-it’s about profit maximization disguised as law. The only thing "successful" here is the lawyers.